- シンクタンクならニッセイ基礎研究所 >

- 経営・ビジネス >

- 雇用・人事管理 >

- Future Issues of Indefinite Employment Reclassification Rule - Learning from the Precedent in South Korea -

Future Issues of Indefinite Employment Reclassification Rule - Learning from the Precedent in South Korea -

生活研究部 上席研究員・ヘルスケアリサーチセンター・ジェロントロジー推進室兼任 金 明中

文字サイズ

- 小

- 中

- 大

Have there been problems by the implementation of the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers? Kim Yuseon (2008) points out that while regular employment is increasing, indirect employment via staffing and temp agencies has been increasing for the same period.

Also, the practice of “hiring cutoff” where an employment contract is terminated before two years elapses, has been widespread. Section 4.2 of the “Act on the Protection of Fixed-Term and Short-Term Workers (the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers)” states that fixed term employees may be employed at most for two years, whereupon they become classified as contractual workers for an indefinite contractual period. However, this can be interpreted to mean that employment may be terminated at any point of time prior to two years. In fact, most workers’ employment contracts were terminated at the point of around 1 year and 9 to 10 months after their contracts were signed. Experts have predicted that this problem would occur ever since the Ministry of Labor first began designing the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers.

It is fair to say that the implementation of the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers in South Korea has had a somewhat positive effect by lowering the ratio of non-regular workers and increasing the usage of nonfixed-term contracts, but the effect has not been as pronounced as the South Korean government had expected. In other words, more and more, as contracts near the two-year point, fixed-term contractors run into the hiring cutoff, and their jobs are outsourced. One typical example, which occurred in June 2007, was the “E-Land War.” Just prior to the implementation of the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers, the E-Land Retail Group, parent of the South Korean retailer “Homever,” announced that 521 of its 1,100 contract workers of over two years would be reclassified as regular employees. However, they also notified 350 people whose contract terms had expired that their contracts would not be renewed, and decided to outsource the jobs such as cash registers, etc. Outraged at this last-minute hiring cutoff, union workers lead by the ajumma (middle-aged women), held labor strikes and sit-ins in protest. The strikes continued for 510 days, finally ending on November 13, 2008. While the “E-Land War” did result in the rehiring of some of the union members who were terminated during the strike after the major distributor Samsung Tesco Homeplus acquired Homever’s business, and as the negotiations continued after the acquisition, some of the non-regular workers were automatically reclassified as indefinite employees during the 16 month-long ordeal; the practice of hiring cutoff to cope with the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers appeared the forefront as a societal problem.

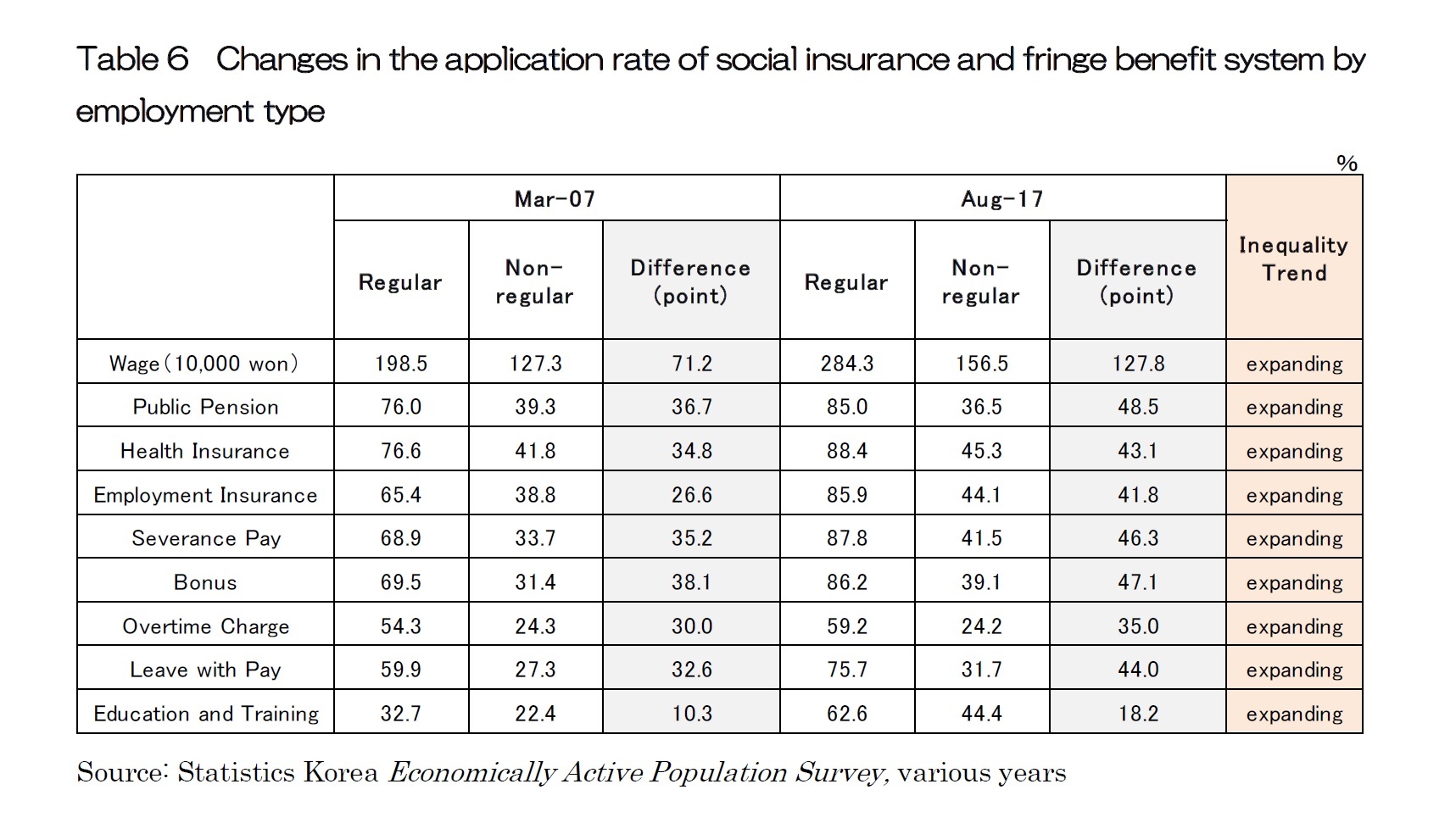

The “E-Land War” has paid the attention of the mass media and the nation as a whole. Although it was resolved in a not altogether unfavorable way, it was a reminder that this problem had gone on unsolved for 10 years, ever since the implementation of the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers. There were still many vulnerable workers in Korean society who, in spite of the unfair termination of their contracts, their poor working conditions, and in spite of being discriminated against merely for being irregular employees, were powerless to do anything at all about it. Further, even those who were reclassified as contractual employees for an indefinite contractual period under the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers saw no improvement in the way they were treated such as many continuing to see a widening salary and benefits gap between themselves and regular workers. This has contributed to growing inequality in South Korean society.

The Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers reclassifies contract workers who have worked for two years or more as contractual employees with no fixed term, requires management to employ them directly, prohibits unreasonable discrimination against them through wages or working conditions, and grants non-regular workers who were discriminated against the right to seek redress before South Korea’s Labor Commission.

However, the reality is that improved treatment of non-regular workers has not improved that much. Currently, only the discriminated individual against has standing to seek redress for discrimination under the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers, and only if the discrimination is unreasonable when compared with a regular employee with the same or similar job duties. Further, very few workers are willing to jeopardize their contracts in order to pursue this remedy.

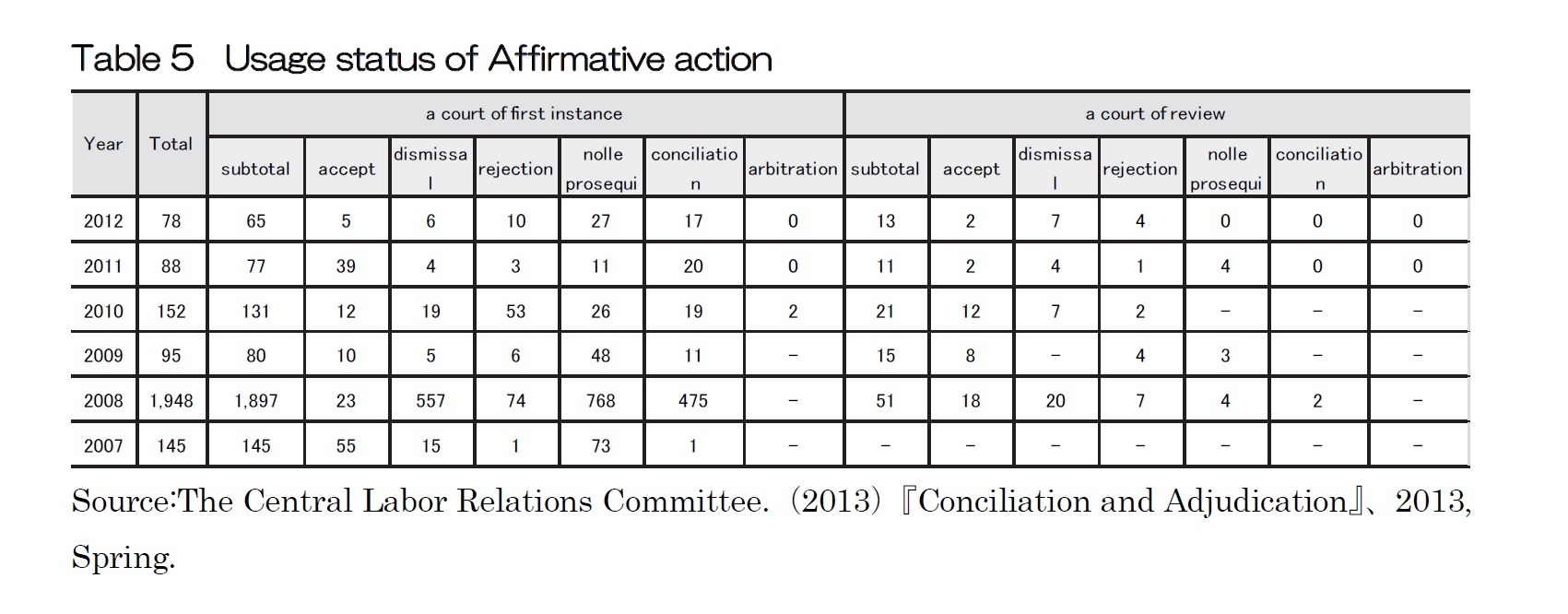

Table 5 shows the state of utilization of this discrimination remedy system, which peaked in 2008, the year after the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers was implemented, at 1,948 petitioners using the system, and has been declining ever since, falling all the way to only 78 cases in 2012. Given the large proportion of non-regular workers in South Korea, the number of cases where the discrimination remedy system has actually been used is profoundly low. Why are there so few cases of the discrimination remedy system being used? The Ministry of Labor announced that it would consider the potentially negative consequences faced by those non-regular workers who individually petition for redress of discrimination, and that it would introduce a method whereby a labor union could represent an individual member as a petitioner, but so far this has not been implemented. Further, even when a petitioner does make a claim, in many cases the commission finds that no discrimination occurred because the scope of regular employees with the same or similar job duties is very narrow. We believe this is the reason for the declining frequency of the use of the discrimination remedy system.

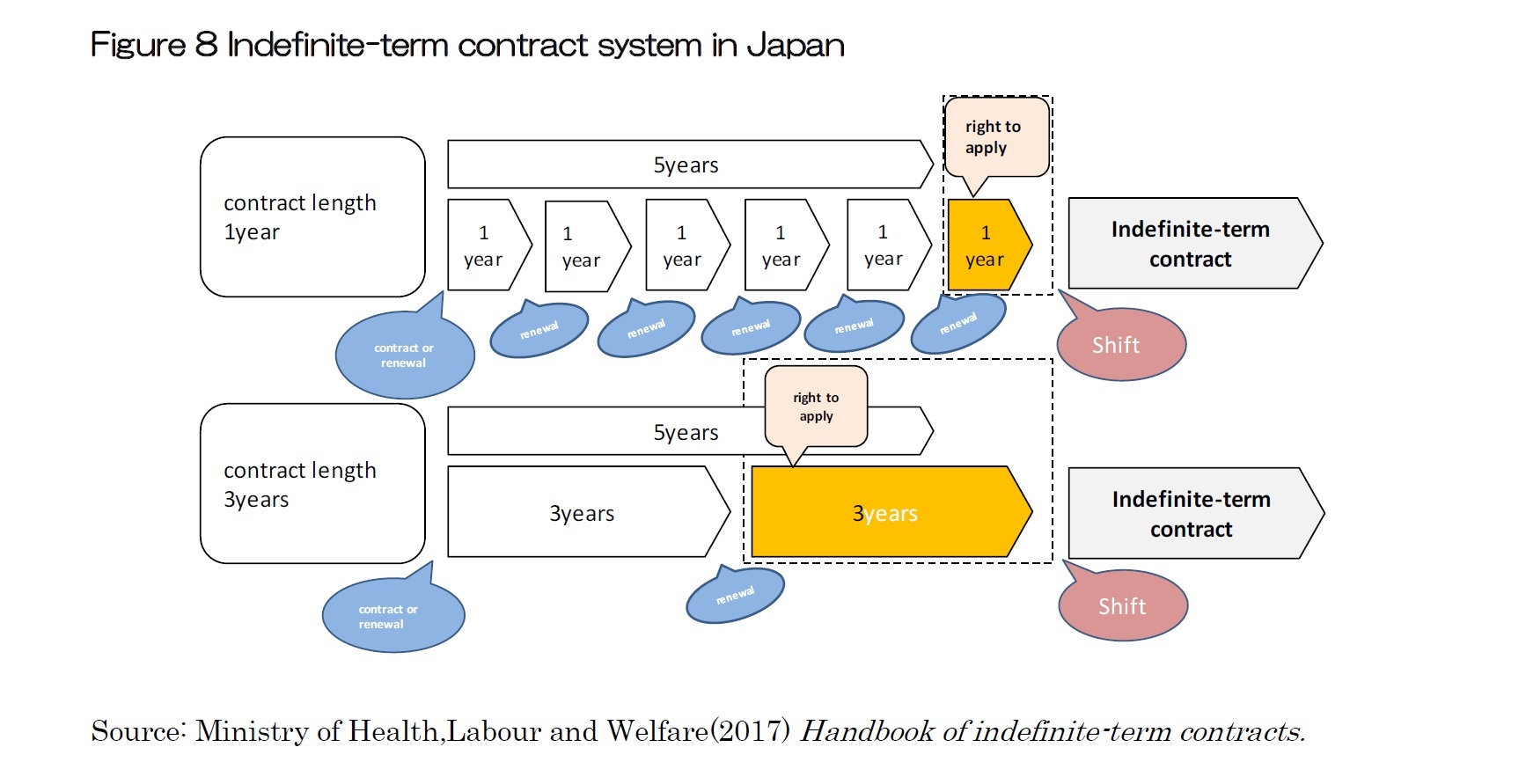

As discussed above, Japan applied its own “indefinite employment reclassification rule” from April 2018(Figure8). In Japan, after the Lehman Shock of 2008, the termination of fixed-term contract workers’ contracts became a societal problem, resulting in the enactment of an “indefinite employment reclassification rule” by the Liberal Democratic Party of Japan’s administration in August of 2012, which was implemented in April of 2013.

※Labor Contract Act Section 18

“If a Worker whose total contract term of two or more fixed-term labor contracts (excluding any contract term which has not started yet; the same applies hereinafter in this Article) concluded with the same Employer (referred to as the "total contract term" in the next paragraph) exceeds five years applies for the conclusion of a labor contract without a fixed term before the date of expiration of the currently effective fixed-term labor contract, to begin on the day after the said date of expiration, it is deemed that the said Employer accepts the said application. In this case, the labor conditions that are the contents of said labor contract without a fixed term are to be the same as the labor conditions (excluding the contract term) of the currently effective fixed-term labor contract (excluding parts separately provided for with regard to the said labor conditions (excluding the contract term)).” Generally, the indefinite employment reclassification rule was sought by part time workers, contract employees, probationary employees, half-time employees, etc.

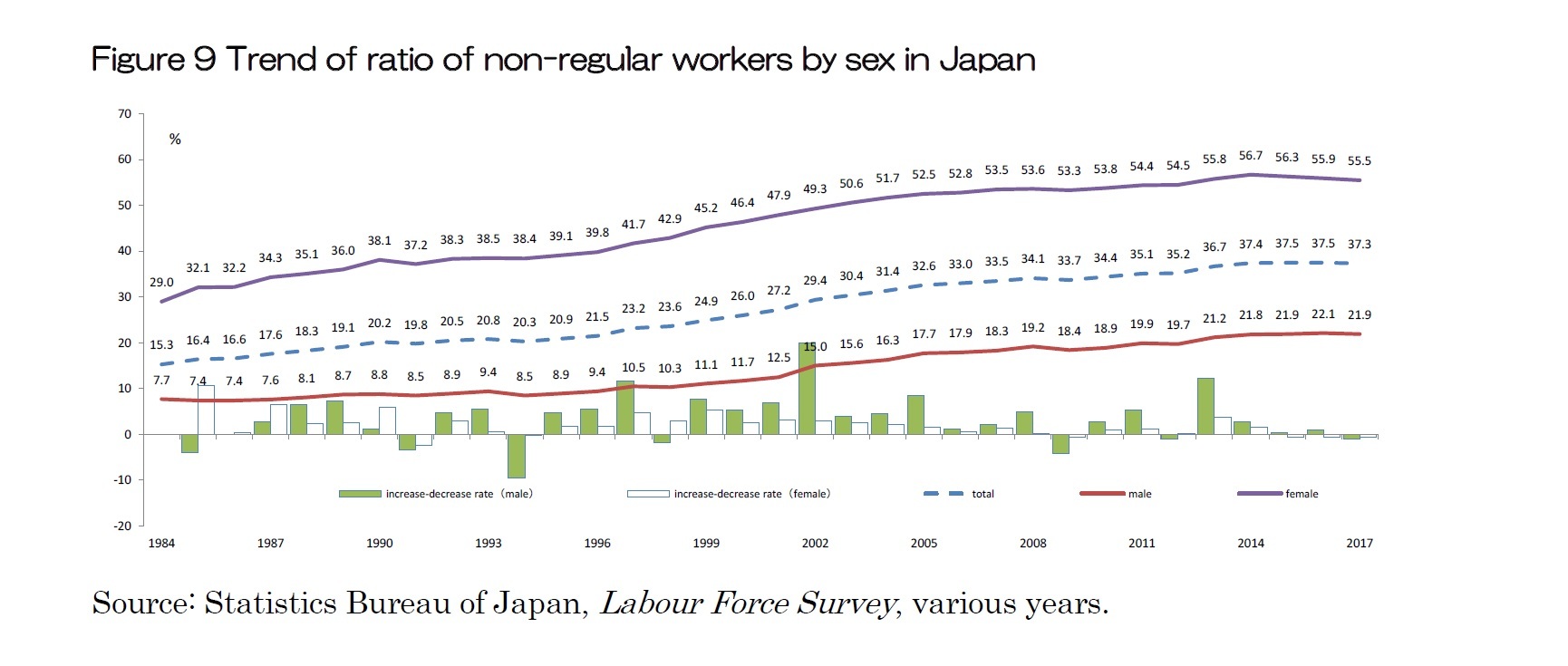

As of 2017, non-regular workers accounted for 37.3% of Japan’s labor force, whose that is still increasing(Figure9). Compared with those of men and women, 55.5% of women were non-regular workers, nut men are a much lower 21.9%. However recently the ratio of irregularly employed men is increasing faster than women’s one.

Toda (2017), using the “State of National Employment Panel Survey 2017,” states that while 8.93 million (46.7% of non-regular workers) non-regular workers working as non-fixed term workers since April 2013 who do not temporarily leave work or become reclassified as regular employees by April 2018 may be subject to the indefinite employment reclassification rule, “a not insignificant number of workers would decline to pursue indefinite employment reclassification, even if they become eligible, because they fear it could change their job responsibilities and/or increase their workload. Furthermore, a not insignificant number of businesses will terminate employment contracts before they exceed five years.” Accordingly, he explains that the actual number of people benefitted by the act will be lower than the number stated above.

Applying Toda’s (2017) analysis to the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ Bureau of Statistics labor survey, one may estimate that, at most, 9.9 million non-regular workers may be subject to the indefinite employment reclassification rule.

The Japanese government’s reason for implementing the indefinite employment reclassification rule is to prevent the abusive use of repeated fixed-term employment contracts to employ workers for long period of time, and by doing so, to protect the job security of fixed-term contract workers. The right to elect reclassification to indefinite employment may be exercised, in the case of a one-year contract, within one year after the fifth contract renewal, or, in the case of a three-year contract, within three years of the second contract renewal. There are no particular requirements for exercising this right—it may be in writing or oral. However, unlike in South Korea as described previously, the reclassification does not occur automatically, and must be invoked by the worker. The indefinite employment contract begins on the day after the contract in effect when the right is invoked expires.

For workers, the benefit of indefinite employment reclassification is job security. On the other hand, from businesses point of view, the benefit is that it makes it relatively easy to acquire indefinite-term contract workers who are experienced and familiar with the business and plan a long-term human personnel retention strategy. However, even after becoming an indefinite-term contract worker, there is no guarantee that wages or work conditions will improve. As a rule, the wages and job treatment will continue as before. Section 20 of the Labor Contract Act states: that a labor condition of a fixed-term labor contract for a Worker is different from the counterpart labor condition of another labor contract without a fixed term for another Worker with the same Employer due to the existence of a fixed term, it is not to be found unreasonable, considering the content of the duties of the Workers and the extent of responsibility accompanying the said duties (hereinafter referred to as the "content of duties" in this Article), the extent of changes in the content of duties and work locations, and other circumstances.” While this disallows differing standards for fixed-term and indefinite-term contract workers, it does not mention of the difference between regular employees and indefinite-term contract workers. If it remains unaddressed, the gap in working conditions between regular employees and indefinite-term contract workers may continue to widen.

Will the practice of “hiring cutoff” occur in Japan as it has in South Korea? In fact it is already occurring in some places in Japan. One such example is University of Tokyo’s “Todai Rule.”

When the University of Tokyo incorporated in 2004, it established the so-called “Todai Rule,” cutting of fixed term employees’ employment at five years. Due to this rule, after working for five years, workers must take a “cooling period” vacation of at least three months. When the Labor Contracts Act was revised in 2013, this “cooling period” was expanded to six months. Due to this, adjunct instructors got to enjoy a six-month sabbatical every five years, but they also lost the opportunity to exercise the right to be reclassified as indefinite-term contractual employees when their continued employment rights were reset during the cooling period. If the “Todai Rule” continues as implemented, there is a high probability that large-scale “hiring cutoff” could occur in April 2018, harming the majority of their approximately 8,000 part-time instructors. Further, if such a policy goes into effect at a prominent national university like the University of Tokyo, the ripple effects on other national universities will be pronounced. The eighty-six national universities in Japan employ at the very least, over 100,000 part-time instructors. The University of Tokyo Faculty and Staff Union and the Union of University Part-Time Lecturers in Tokyo Area have appeared with measures. They claim that the “Todai Rule” is illegal, and are prepared to take legal action if the university does not change its policy. The unions have put particular emphasis on Section 90.1 of the Labor Standards Act, claiming that the “Todai Rule” is not in compliance with it.

Section 90.1 of the Labor Standards Act states “In drawing up or changing the rule of employment, the Employer shall ask the opinion of either a labor union organized by a majority of the Workers at the workplace concerned (in cases where such labor union exists), or a person representing a majority of the workers (in cases where such union does not exist).”

Further, in a global ranking of universities, one reason for the University of Tokyo being downgraded was their lack of female instructors. If the hiring cutoff practices against the proportionally high number of irregularly employed women are not changed, the university’s reputation may decline further.

In the face of these problems, the university announced an end to this employment policy on December 2, 2017. As a result, a path to reclassification to indefinite-term contractual employment has opened up for approximately 11,000 adjunct instructors.

Although the University of Tokyo may have solved its problems, the practice of hiring cutoff continues at many other universities like Tohoku University. One hopes that the University of Tokyo’s example will have a positive impact on other universities in this regard.

Ten years have already elapsed since South Korea introduced its Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers. Since this new system has been implemented, socio-economic changes and the impact of the system have somewhat reduced the ratio of non-regular workers in the workplace, but non-regular workers still account for over 30% of all jobs. Further, the malignant practice of hiring cutoff remains as it is. Even those who have been reclassified as indefinite-term contractual workers due to the implementation of the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers have seen no improvement in their working conditions, and many are faced with an increasingly wide gap in wages and benefits when compared with regular employees.

In Japan as well the ratio of non-regular workers continues to increase, with no improvement in the working conditions of non-regular workers.

Improving working conditions for non-regular workers, in December of 2016 the Japanese government presented a “Guidelines for Equal Pay for Equal Work Proposal” at the “Council for the Realization of Work Style Reform,” with case studies of unreasonable discrimination against non-regular workers. However, it is still unclear when this system will be implemented. Specifically, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare planned to implement “equal pay for equal work” in accordance with the “Guidelines for Equal Pay for Equal Work Proposal” starting from 2019. However, on February 7 of this year, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare announced that the start date in the work style reform bill, it will submit to the Diet, has been pushed back by roughly one year. Furthermore, recently discrepancies were discovered in the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s “flex-time” working hours survey, causing the ministry to indefinitely postpone submission to the Diet of work-style reform bills based on “equal pay for equal work” and “limiting overtime hours.” Improvement in working conditions for non-regular workers still seems to be a distant goal.

Further, reference to the South Korean developments introduced in this paper suggests that it is likely that Japan will also experience the same outbreak of hiring cutoffs just prior to the application of an indefinite employment reclassification rule. However, where the Lehman Shock financial crisis struck South Korea immediately after it implemented its indefinite employment reclassification rule, Japan is currently experiencing a critical labor shortage, suggesting that hiring cutoffs will not be as pronounced as they were in South Korea. Still, hiring cutoffs are already occurring sporadically in Japan. An additional problem is that there is no solution in sight for the lack of improved working conditions for indefinite-term contractual employees. Even though Section 20 of Japan’s Labor Contracts Act prohibits discrimination against fixed-term contract workers as compared with indefinite-term contract workers, it does not address discrimination against indefinite-term contract workers as compared against regular employees. In other words, while the “indefinite employment reclassification rule” being implemented in April 2018 will provide job security, it will not otherwise guarantee improved working conditions for indefinite-term contract workers.

Even if hiring cutoff is not as severe as it was in South Korea, it is feared that neglecting to take measures to improve working conditions for indefinite-term contract workers will create new disparities between indefinite-term contract workers and regular employees. We continue to monitor what measures the Japanese and South Korean governments will take to improve working conditions for non-regular workers and indefinite-term contract workers.

Japanese

- 大沢真知子・金明中(2009)「労働力の非正規化の日韓比較-その要因と社会への影響」ニッセイ基礎研所報Vol55.2009 Autumn

- 大沢真知子・金明中「経済のグローバル化にともなう労働力の非正規化の要因と政府の対応の日韓比較」『日本労働研究雑誌』Vol.52,特別号

- 厚生労働省(2018)「無期転換ルール ハンドブック」:Ministry of Health,Labour and Welfare(2018) Handbook of indefinite-term contracts.

- 総務省統計局(2018)「労働力調査の結果を見る際のポイント No.19」

- 総務省統計局「労働力調査」:Statistics Bureau of Japan, Labour Force Survey, various years.

- 戸田淳仁(2017)「無期転換ルールに当てはまる⼈はどれくらいいるか」

- リクルートワークス研究所(2017)「全国就業実態パネル調査2017」

Korean

- Byeong-Hee, Lee(2008) Effect of Employment in One Year of the Enforcement of the Act on the Protection of Non-Regular Workers

- Kim Yusun(2017)「The scale of non-regular workers in South Korea 2017.08」

- Statistics Korea Economically Active Population Survey, various years

- The Central Labor Relations Committee.(2013)『Conciliation and Adjudication』、2013, Spring.

(2019年03月26日「基礎研レポート」)

生活研究部 上席研究員・ヘルスケアリサーチセンター・ジェロントロジー推進室兼任

金 明中 (きむ みょんじゅん)

研究・専門分野

高齢者雇用、不安定労働、働き方改革、貧困・格差、日韓社会政策比較、日韓経済比較、人的資源管理、基礎統計

03-3512-1825

- プロフィール

【職歴】

独立行政法人労働政策研究・研修機構アシスタント・フェロー、日本経済研究センター研究員を経て、2008年9月ニッセイ基礎研究所へ、2023年7月から現職

・2011年~ 日本女子大学非常勤講師

・2015年~ 日本女子大学現代女性キャリア研究所特任研究員

・2021年~ 横浜市立大学非常勤講師

・2021年~ 専修大学非常勤講師

・2021年~ 日本大学非常勤講師

・2022年~ 亜細亜大学都市創造学部特任准教授

・2022年~ 慶應義塾大学非常勤講師

・2019年 労働政策研究会議準備委員会準備委員

東アジア経済経営学会理事

・2021年 第36回韓日経済経営国際学術大会準備委員会準備委員

【加入団体等】

・日本経済学会

・日本労務学会

・社会政策学会

・日本労使関係研究協会

・東アジア経済経営学会

・現代韓国朝鮮学会

・博士(慶應義塾大学、商学)

金 明中のレポート

| 日付 | タイトル | 執筆者 | 媒体 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2025/07/08 | 「静かな退職」と「カタツムリ女子」の台頭-ハッスルカルチャーからの脱却と新しい働き方のかたち | 金 明中 | 基礎研マンスリー |

| 2025/06/06 | “サヨナラ”もプロに任せる時代-急増する退職代行サービス利用の背景とは? | 金 明中 | 基礎研マンスリー |

| 2025/06/02 | 日韓カップルの増加は少子化に歯止めをかけるか? | 金 明中 | 研究員の眼 |

| 2025/05/22 | 【アジア・新興国】韓国の生命保険市場の現状-2023年のデータを中心に- | 金 明中 | 保険・年金フォーカス |

新着記事

-

2025年11月04日

数字の「26」に関わる各種の話題-26という数字で思い浮かべる例は少ないと思われるが- -

2025年11月04日

ユーロ圏消費者物価(25年10月)-2%目標に沿った推移が継続 -

2025年11月04日

米国個人年金販売額は2025年上半期も過去最高記録を更新-但し保有残高純増は別の課題- -

2025年11月04日

パワーカップル世帯の動向(2)家庭と働き方~DINKS・子育て・ポスト子育て、制度と夫婦協働が支える -

2025年11月04日

「ブルー寄付」という選択肢-個人の寄付が果たす、資金流入の突破口

お知らせ

-

2025年07月01日

News Release

-

2025年06月06日

News Release

-

2025年04月02日

News Release

【Future Issues of Indefinite Employment Reclassification Rule - Learning from the Precedent in South Korea -】【シンクタンク】ニッセイ基礎研究所は、保険・年金・社会保障、経済・金融・不動産、暮らし・高齢社会、経営・ビジネスなどの各専門領域の研究員を抱え、様々な情報提供を行っています。

Future Issues of Indefinite Employment Reclassification Rule - Learning from the Precedent in South Korea -のレポート Topへ

各種レポート配信をメールでお知らせ。読み逃しを防ぎます!

各種レポート配信をメールでお知らせ。読み逃しを防ぎます!