- シンクタンクならニッセイ基礎研究所 >

- 経済 >

- 日本経済 >

- Japan's Productivity through the Lens of “Cheap Japan”

2023年08月22日

文字サイズ

- 小

- 中

- 大

2|Data Verification

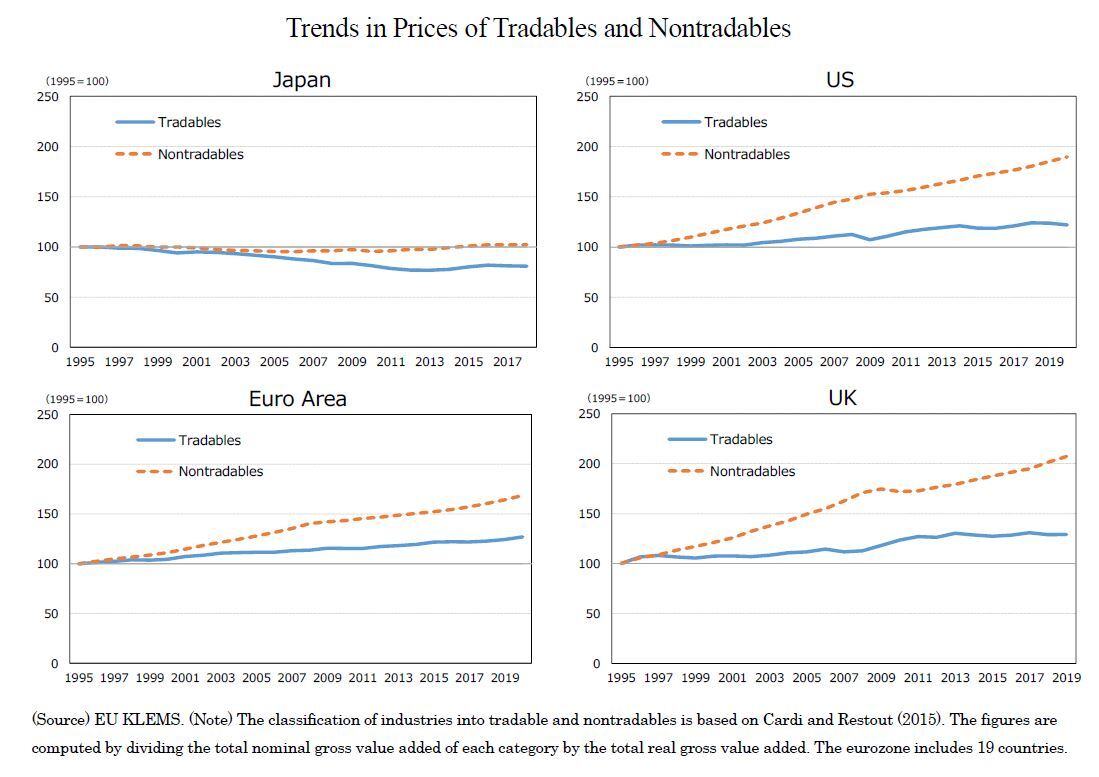

This section examines whether the Balassa–Samuelson hypothesis aligns with the empirical data. To start, we analyze data on prices, wages, and productivity for both tradables and nontradables in Japan and other countries. However, precisely distinguishing industries between tradables and nontradables is not always straightforward. While manufacturing is generally considered a tradable industry and services as nontradable, some services such as internet-based services easily transcend national borders. For this study, we follow the classification by Cardi and Restout (2015) to categorize industries of tradables and those of nontradables.10We utilize data from the EU KLEMS database for Japan, the United States, the euro area, and the United Kingdom.

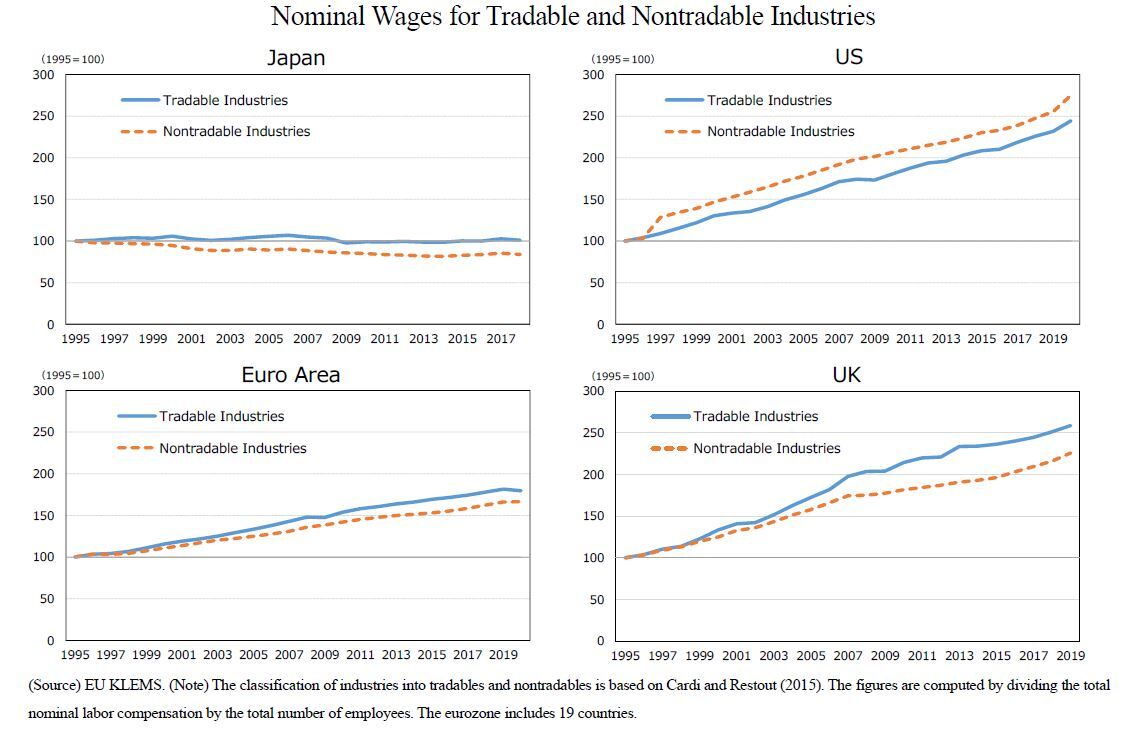

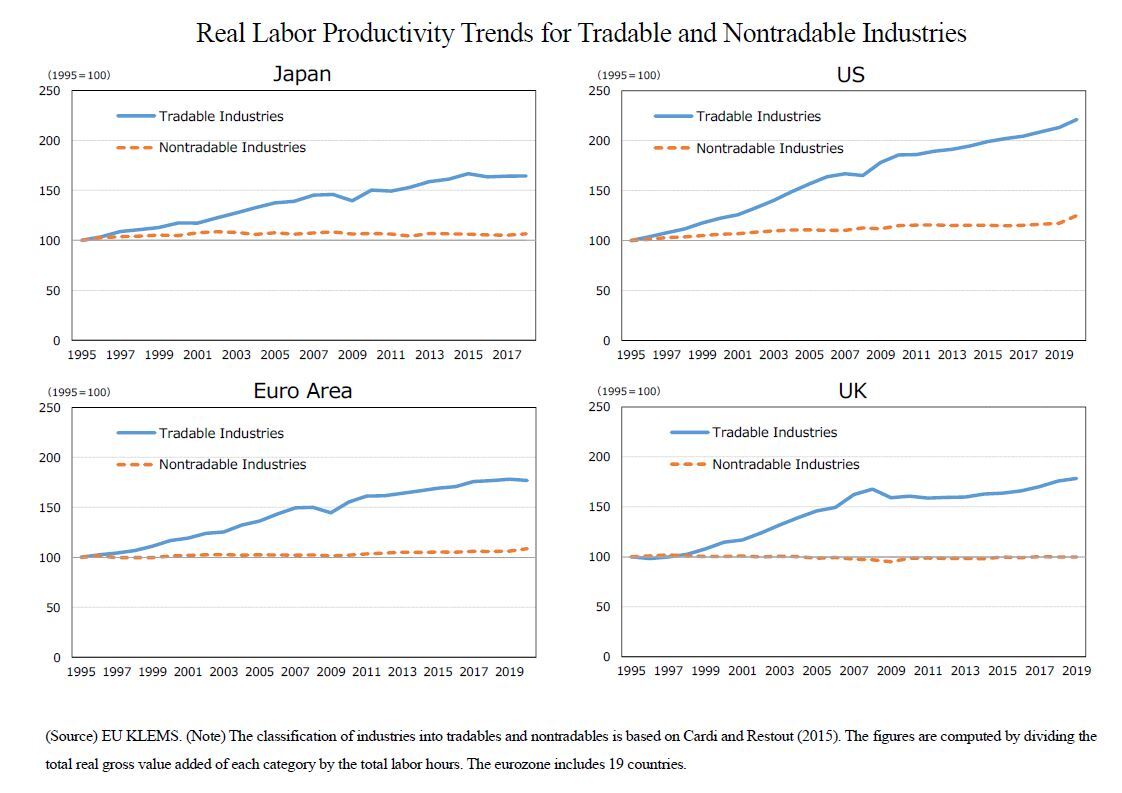

To calculate prices of tradables and nontradables, we divided the total nominal gross value added of each industry by the total real gross value added. Nominal wages were determined by dividing the total compensation of employers in the tradable and nontradable industries by the total number of employees. Regarding productivity, real labor productivity was computed by dividing the total real gross value added of the industries by the total labor input (i.e., the total hours worked by employees). 11

Upon analyzing the price trends of tradables and nontradables, it becomes evident that in the United States, the euro area, and the United Kingdom, prices for both tradables and nontradables have been continuously increasing, with nontradables experiencing a particularly substantial price surge. Conversely, in Japan, the prices of tradables experienced a decline until the mid-2010s, stabilizing thereafter, while the prices of nontradables have remained relatively steady and flat since 1995, representing a marked contrast.

This section examines whether the Balassa–Samuelson hypothesis aligns with the empirical data. To start, we analyze data on prices, wages, and productivity for both tradables and nontradables in Japan and other countries. However, precisely distinguishing industries between tradables and nontradables is not always straightforward. While manufacturing is generally considered a tradable industry and services as nontradable, some services such as internet-based services easily transcend national borders. For this study, we follow the classification by Cardi and Restout (2015) to categorize industries of tradables and those of nontradables.10We utilize data from the EU KLEMS database for Japan, the United States, the euro area, and the United Kingdom.

To calculate prices of tradables and nontradables, we divided the total nominal gross value added of each industry by the total real gross value added. Nominal wages were determined by dividing the total compensation of employers in the tradable and nontradable industries by the total number of employees. Regarding productivity, real labor productivity was computed by dividing the total real gross value added of the industries by the total labor input (i.e., the total hours worked by employees). 11

Upon analyzing the price trends of tradables and nontradables, it becomes evident that in the United States, the euro area, and the United Kingdom, prices for both tradables and nontradables have been continuously increasing, with nontradables experiencing a particularly substantial price surge. Conversely, in Japan, the prices of tradables experienced a decline until the mid-2010s, stabilizing thereafter, while the prices of nontradables have remained relatively steady and flat since 1995, representing a marked contrast.

Regarding the trend in nominal wages, we observe that wages in Japan have generally remained stable in the tradable industries, while they have tended to decline in nontradable industries. On the other hand, in the United States, the euro area, and the United Kingdom, wages have continued to rise in both tradable and nontradable industries.

10The industries classified as tradable include “agriculture, forestry, and fishing”, “mining and quarrying”, “manufacturing”, “transportation and storage”, “information and communication”, and “financial and insurance activities”. On the other hand, the nontradable industries encompass “electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply”, “water supply; sewerage, waste management, and remediation activities”, “construction”, “wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles”, “accommodation and food service activities”, “real estate activities”, “professional, scientific, and technical activities; administrative and support service activities”, “public administration and defense; compulsory social security”, “education”, “human health and social work activities”, “arts, entertainment and recreation”, and “other service activities”.

11In this study, we have chosen to concentrate on labor productivity as a productivity metric due to its ease of measurement. Note, however, that productivity is ideally assessed using total factor productivity, which accounts for both labor and capital inputs. Labor productivity is influenced by both total factor productivity and the level of capital per worker. In the context of Japan, there has been a noticeable decline in the investment rate (the ratio of capital investment to GDP), coupled with sluggish growth in private capital stock. These developments have raised concerns about their potential impact on economic growth (Hiraguchi, 2022).

3|Implications for Japan

Based on the presented data, we rigorously explore the implications for the development of Japan's real exchange rate. Specifically, we focus on the difference in the dynamics of prices and wages between Japan's tradable and nontradable industries. Since the late 1990s, the economic landscape in Japan has undergone substantial changes due to economic globalization, with a notable expansion of trade involving China and other emerging Asian economies. As a result, Japan's tradable industries have encountered fierce price competition, leading to a state of price stagnation for tradables. Concurrently, the tradable industries experienced a downturn, prompting a significant workforce migration from these industries to the nontradable industries, consequently resulting in a decline in wages in nontradable industries. This phenomenon led to the moderation of wages in the nontradable industries, preventing substantial price increases for nontradable.12Despite witnessing an increase in real labor productivity in Japan's tradable industries, the negative impact of declining labor input (total hours worked by workers) outweighed the positive effect of value-added growth. Consequently, the overall value added proved insufficient to stimulate significant changes in prices.

Based on the presented data, we rigorously explore the implications for the development of Japan's real exchange rate. Specifically, we focus on the difference in the dynamics of prices and wages between Japan's tradable and nontradable industries. Since the late 1990s, the economic landscape in Japan has undergone substantial changes due to economic globalization, with a notable expansion of trade involving China and other emerging Asian economies. As a result, Japan's tradable industries have encountered fierce price competition, leading to a state of price stagnation for tradables. Concurrently, the tradable industries experienced a downturn, prompting a significant workforce migration from these industries to the nontradable industries, consequently resulting in a decline in wages in nontradable industries. This phenomenon led to the moderation of wages in the nontradable industries, preventing substantial price increases for nontradable.12Despite witnessing an increase in real labor productivity in Japan's tradable industries, the negative impact of declining labor input (total hours worked by workers) outweighed the positive effect of value-added growth. Consequently, the overall value added proved insufficient to stimulate significant changes in prices.

On the contrary, in the United States, the euro area, and the United Kingdom, the growth of real labor productivity in the tradable industries was predominantly fueled by value-added expansion. While these countries would have faced comparable influences from the growth of the tradable industries in China and other emerging Asian economies, both the prices and wages within their respective tradable industries exhibited an upward trend.13

On the contrary, in the United States, the euro area, and the United Kingdom, the growth of real labor productivity in the tradable industries was predominantly fueled by value-added expansion. While these countries would have faced comparable influences from the growth of the tradable industries in China and other emerging Asian economies, both the prices and wages within their respective tradable industries exhibited an upward trend.13

When examining this aspect, it is evident that the United States, the euro area, and the United Kingdom may have made notable advancements in product differentiation through technological innovation and new product development. For instance, the Cabinet Office (2011) highlights contrasting trends in terms of trade (the ratio of export prices to import prices) between Japan and Germany, two countries with similar industrial structures. The report suggests that Germany has a higher proportion of intra-industry trade, wherein goods from the same industry are both exported and imported, indicating significant progress in product differentiation. This progress in product differentiation empowers Germany to more effectively pass on the price increases of raw materials, such as natural resources, to the prices of its export goods.

When examining this aspect, it is evident that the United States, the euro area, and the United Kingdom may have made notable advancements in product differentiation through technological innovation and new product development. For instance, the Cabinet Office (2011) highlights contrasting trends in terms of trade (the ratio of export prices to import prices) between Japan and Germany, two countries with similar industrial structures. The report suggests that Germany has a higher proportion of intra-industry trade, wherein goods from the same industry are both exported and imported, indicating significant progress in product differentiation. This progress in product differentiation empowers Germany to more effectively pass on the price increases of raw materials, such as natural resources, to the prices of its export goods.The data do not provide explicit evidence of a direct shift of workers to the tradable industries in pursuit of higher wages. However, considering the persistent stagnation of labor productivity in the nontradable industries and the growing workforce in the industries, driven by factors such as the ongoing shift of the economy toward services, it is plausible to consider that higher wages in the tradable industries might have influenced the rise in wages within the nontradable industries. This relationship implies the possibility of a spillover effect from the wage increase in the tradable industries to wages in the nontradable industries, subsequently leading to an increase in prices in the nontradable industries.

In Japan, prices of nontradables remained unchanged, while in the United States, the euro area, and the United Kingdom, they experienced an upward trajectory. This disparity contributed significantly to the depreciation trend observed in the Japanese real exchange rate. The validity of this interpretation requires further elaboration

Nevertheless, as mentioned above, if the depreciation of Japan's real exchange rate, commonly referred to as “cheap Japan”, is indeed a result of the failure of Japan's tradable industries to generate sufficient value added relative to its overseas counterparts, and this deficiency is due to a lack of innovation in new product development and product differentiation, then the “cheap Japan” phenomenon should be viewed as a warning to Japan's tradable industries.

12 Japan is notable among advanced countries for its pronounced tendency to exercise significant restraint in implementing price increases in response to rising production costs, including soaring commodity prices. This cautious approach toward raising prices has resulted in income leakage to foreign markets and is also considered to have played a role contributing to wage reductions (Saito, 2023).

13 The Balassa–Samuelson hypothesis posits that tradables adhere to the law of one price. However, empirical evidence indicates that while the prices of Japan's tradables have been declining, the prices of tradables in Europe and the United States have been rising. This observation presents several potential explanations, including disparities in the competing tradables between Japan and Europe/United States, as well as variations in the level of competition. As noted in footnote 7, companies employ pricing-to-market strategies, which potentially challenges the applicability of the law of one price to tradables. This observation could imply that tradable industries in Europe and the United States have experienced increased markups while Japan witnessed a decrease in markups. Notably, Nakamura and Ohashi (2019) have highlighted that advanced countries tend to exhibit an increasing trend in markups, whereas Japan does not display the same upward trend.

Ⅳ. The Relationship Between the Real Exchange Rate and Productivity: The Balassa- Samuelson Hypothesis

This paper confirmed that prices in Japan have become cheaper. The relationship between the real exchange rate and productivity was examined through the Balassa–Samuelson hypothesis. The paper also pointed out that the long-term depreciation trend of the real exchange rate, or the “cheap Japan” phenomenon, was caused by the failure of Japan's tradable industries to generate sufficient value added amid economic globalization and the migration of workers from tradable to nontradable industries, which led to lower wages in nontradable industries and prevented the prices from rising.

Lower prices have the benefit of increasing Japan's attractiveness as a production location and drawing more foreign tourists. In particular, an increase in foreign direct investment will provide an opportunity to acquire superior foreign technology and promote innovation.

If the decline in Japan's ability to add value in the tradable industries is a challenge for Japan, the country must improve its competitiveness in non-price aspects through product differentiation and the development of new products while taking advantage of “cheap Japan”.

Lower prices have the benefit of increasing Japan's attractiveness as a production location and drawing more foreign tourists. In particular, an increase in foreign direct investment will provide an opportunity to acquire superior foreign technology and promote innovation.

If the decline in Japan's ability to add value in the tradable industries is a challenge for Japan, the country must improve its competitiveness in non-price aspects through product differentiation and the development of new products while taking advantage of “cheap Japan”.

(References.)

Cabinet Office (2011). World Economic Trends 2011 I.

Cardi, O., and Restout, R. (2015). Imperfect Mobility of Labor Across Sectors: A Reappraisal of the Balassa–Samuelson effect. Journal of International Economics, 97(2), 249-265.

Hiraguchi, R. (2022). An Introduction to Japan's Economic Growth. Nihon Keizai Shimbun Shuppan.

Ito, T. (2022). Why Is Japan So Cheap? Project Syndicate, 2022.3.3.

Itskhoki, O. (2021). The Story of the Real Exchange Rate. Annual Review of Economics, 1, 423-455.

Kawai, M., Kasuya, M., and Hiragata, N. (2003). An Analysis of Relative Prices of Nontradable Goods in the G7 Countries. Bank of Japan Working Paper Series. No.03-J-8.

Nakamura, T., and Ohashi, H. (2019). Linkage of Markups Through Transaction. in RIETI Discussion Paper Series, 19-E-107.

Saito, M. (2023). Shouldn't Japanese Consumers and Workers Welcome Price Hikes? Weekly Economist, April 4, 2023, 62-63.

Schmitt-Grohé, S., Uribe, M., and Woodford, M. (2022). International Macroeconomics: A Modern Approach. Princeton University Press.

Shimizu, J., Ohno, S., Matsubara, S., and Kawasaki, K. (2016). In-depth Explanation of International Finance: From Theory to Practice. Nippon Hyoronsha.

Watanabe, T. (2023). The Mystery of World Inflation. Kodansha.

(2023年08月22日「基礎研レポート」)

山下 大輔

山下 大輔のレポート

| 日付 | タイトル | 執筆者 | 媒体 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023/08/22 | Japan's Productivity through the Lens of “Cheap Japan” | 山下 大輔 | 基礎研レポート |

| 2023/07/26 | 日本の物価は持続的に上昇するか-消費者物価の今後の動向を考える | 山下 大輔 | ニッセイ基礎研所報 |

| 2023/07/10 | 景気ウォッチャー調査(23年6月)~景況感の回復ペースが鈍化 | 山下 大輔 | 経済・金融フラッシュ |

| 2023/06/08 | 景気ウォッチャー調査(23年5月)~現状判断DIは4か月連続で上昇 | 山下 大輔 | 経済・金融フラッシュ |

新着記事

-

2025年11月07日

次回の利上げは一体いつか?~日銀金融政策を巡る材料点検 -

2025年11月07日

個人年金の改定についての技術的なアドバイス(欧州)-EIOPAから欧州委員会への回答 -

2025年11月07日

中国の貿易統計(25年10月)~輸出、輸入とも悪化。対米輸出は減少が続く -

2025年11月07日

英国金融政策(11月MPC公表)-2会合連続の据え置きで利下げペースは鈍化 -

2025年11月06日

世の中は人間よりも生成AIに寛大なのか?

お知らせ

-

2025年07月01日

News Release

-

2025年06月06日

News Release

-

2025年04月02日

News Release

【Japan's Productivity through the Lens of “Cheap Japan”】【シンクタンク】ニッセイ基礎研究所は、保険・年金・社会保障、経済・金融・不動産、暮らし・高齢社会、経営・ビジネスなどの各専門領域の研究員を抱え、様々な情報提供を行っています。

Japan's Productivity through the Lens of “Cheap Japan”のレポート Topへ

各種レポート配信をメールでお知らせ。読み逃しを防ぎます!

各種レポート配信をメールでお知らせ。読み逃しを防ぎます!