- シンクタンクならニッセイ基礎研究所 >

- 金融・為替 >

- 金融政策 >

- Reflections on Financial Regulators’ Initial Responses to COVID-19

Reflections on Financial Regulators’ Initial Responses to COVID-19

氷見野 良三

文字サイズ

- 小

- 中

- 大

1――Four concerns

The financial sector policy makers had to address the following four concerns to attain this aim.

(1). Operational risks

Regulators were concerned that the infection and public health policy measures such as lockdowns may disrupt the business continuity of financial institutions. They were also concerned that dependencies on remote work may increase the vulnerability against cyber and IT incidents.

(2). Credit crunch

Bankers are said to lend umbrellas on sunny days and take them back on rainy days. If bankers become excessively risk-averse, healthy corporations and households that face temporary cash shortages but have good prospects of recovering after the pandemic could unnecessarily go bankrupt. Households could be forced to sell their residences or face an impaired credit record and lose future recovery opportunities.

Regulators were also concerned whether the financial system could bear the shock.

(3). Market and liquidity risks

Financial institutions might incur losses due to increased market volatility arising from uncertain economic prospects. Market participants may become cautious about the counterparties’ credit standing and their own funding, refraining from purchasing assets and consequently lowering market liquidity. Declines in market liquidity aggravate the funding liquidity of entities as they cannot obtain cash by selling assets. Funding fears could lead to a run on the capital market.

(4). Solvency risks

If the COVID-19 pandemic continues to deprive corporations and households of revenues, banks’ loans to them may soar and the solvency of banks might be impaired. Problems at banks can exacerbate the credit crunch, market volatility, and liquidity shortages. A vicious circle between financial and economic crises could then be triggered.

Initially, COVID-19 was considered an issue unique to China, but the second week of March 2020 saw a sudden change in perceptions. New York State declared an emergency on Saturday, March 7, 2020. Italy started a lockdown on Monday, March 9, and the World Health Organization declared a pandemic on Wednesday, March 11. U.S. President Donald Trump declared an emergency on Friday, March 13.

Regulatory authorities globally started to explore responses in financial sector policies while facing uncertainties over

・How long the pandemic would persist

・Whether a second or third wave would come

・When vaccines and remedies would become available

・How effective vaccines would be

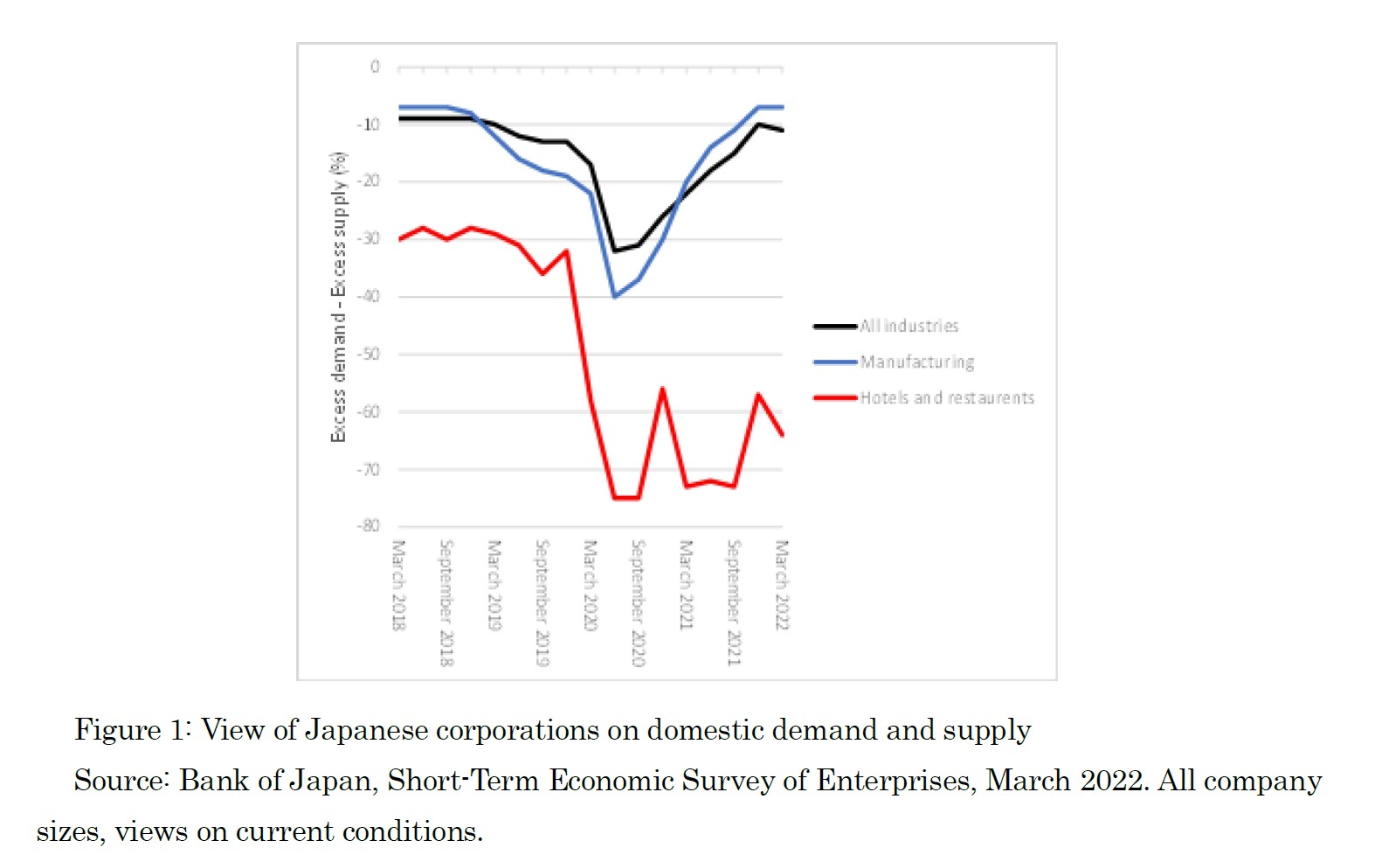

・How the pandemic would affect supply and demand

・What the post-COVID-19 economy and society would be like.

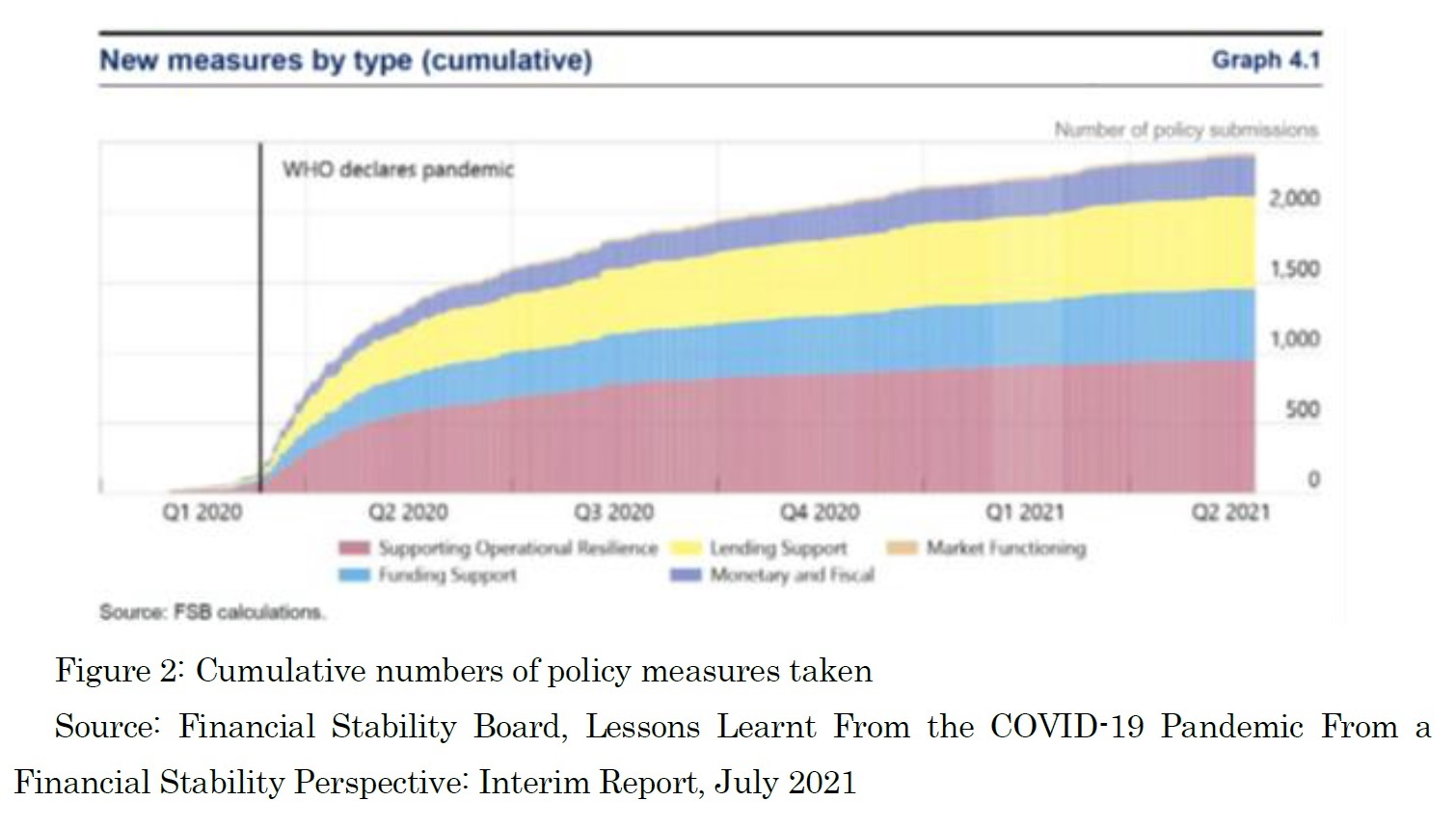

Despite the uncertainties, regulators acted promptly. Figure 2 shows the changes in the cumulative numbers of policy measures taken. According to the FSB, “The speed, scale and scope of the policy response to COVID-19 was without precedent.” 1Indeed, within a month from the second week of March 2020, more than 1,000 new measures were taken ranging from those supporting operational resilience (red) to lending support (yellow), funding support (blue), monetary and fiscal policy measures (purple), and those related to market functioning (brown).

1 Financial Stability Board, Lessons Learnt From the COVID‑19 Pandemic From a Financial Stability Perspective: Interim Report, July 2021.

2――Responses to address operational risk concerns

National authorities took the following types of measures to reduce regulatory and supervisory burdens on financial institutions so that they could concentrate the available resources on activities indispensable for customers:

- Postponing the scheduled implementation of new international standards. For example, the JFSA announced on May 30, 2020, to extend the domestic implementation of the finalized Basel III standards by one year, in line with the agreement of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision.3

- Extending deadlines for reporting to the authorities and for public disclosure. For example, the JFSA announced on the same day that it would flexibly treat the deadlines.

- Postponing on-site inspection. For example, the JFSA started to postpone on-site inspections in the latter half of February 2020.

- Replacing face-to-face processes with virtual interactions. For example, the JFSA started to attempt remote inspections in the second half of February 2020.

Regulators also requested the following from financial institutions to ensure business continuity:

- Producing business continuity plans to prepare for a further spread of infections. In Japan, plans that had been in place to prepare for earthquakes and novel influenza were found to be useful.

- Preparing for cyberattacks and IT systems disruptions. The JFSA hosted an industry-wide war game in a remote working environment in October 2020.

Though lockdowns and other public health measures lasted much longer than initially expected, financial institutions and market infrastructure succeeded in effectively addressing operational risk concerns. Despite surging business activities including the provision of bridge loans and underwriting of bonds, business continuity was largely maintained. Ransomware incidents are on the increase, but cyberattacks have thus far not caused a major disruption of financial functions.

Dedicated efforts by financial institutions made these outcomes possible. The lessons of 9/11 resulted in better preparedness for remote working in the United States. In Japan, the pandemic advanced digitalization and remote working.

2 Financial Stability Board, FSB members take action to ensure continuity of critical financial services functions, April 2, 2020.

3 Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Governors and Heads of Supervision announce deferral of Basel III implementation to increase operational capacity of banks and supervisors to respond to COVID‑19, March 27, 2020.

3――Responses to address market and liquidity risks

The market became volatile in late February 2020 and started to panic in mid-March when the lockdown was implemented in Europe and the United States. Market participants dashed for cash, exchanging U.S. treasuries, gold, and Japanese yen, which had been thought to be safe assets, into cash dollars. This run on the market resulted in the termination of new issues of corporate bonds, near depletion of cash for redemption of investment funds, and the choking of funding in U.S. dollars outside the United States.

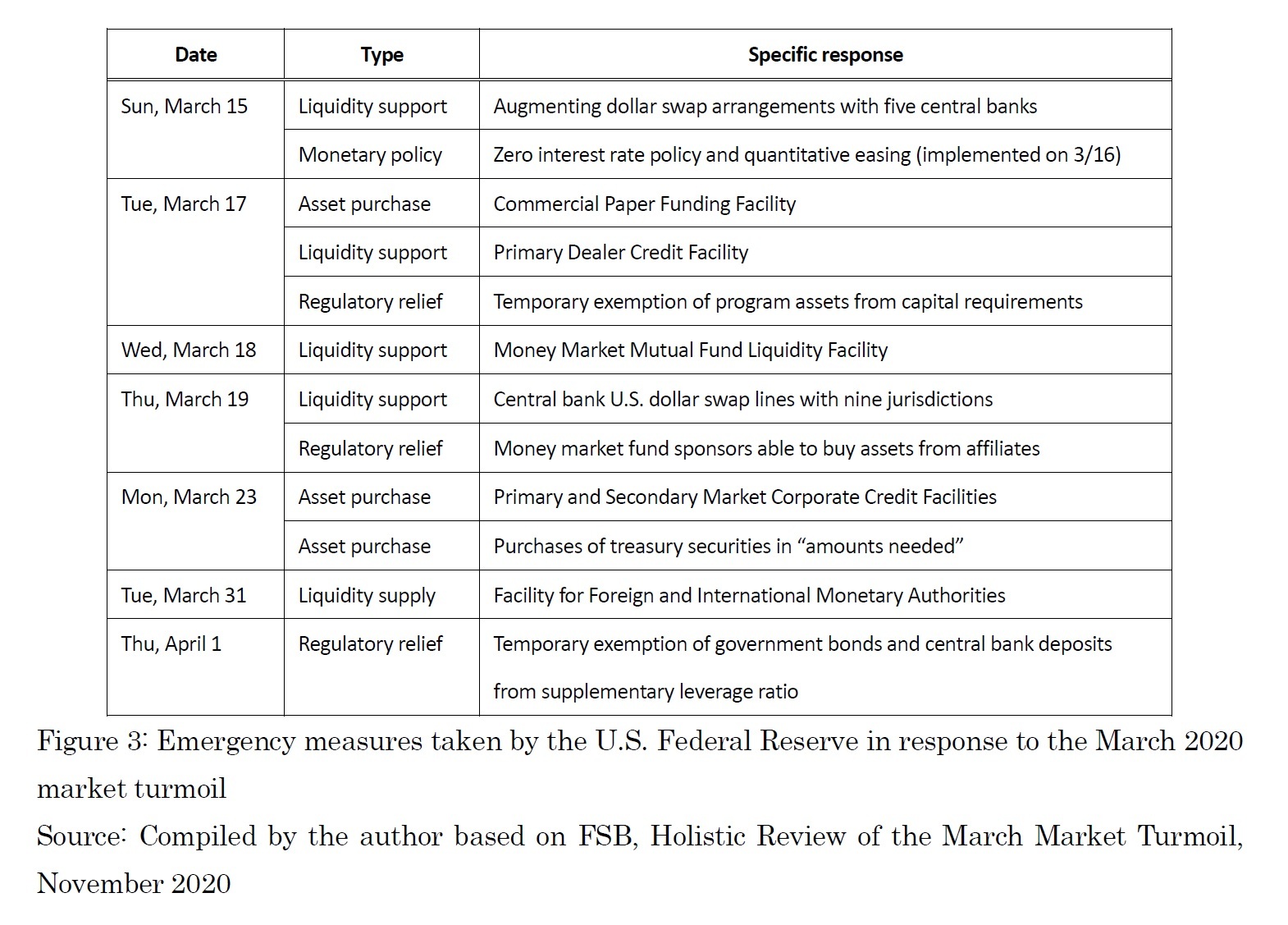

The U.S. Federal Reserve commenced a blitzkrieg in response to this development, launching new measures daily from Sunday, March 15, and exhausting the playbook developed during the global financial crisis (GFC), as Exhibit 3 shows.

Other central banks’ activities were also agile and powerful. For example, the Bank of Japan announced on Monday, March 16, that it enhanced supply of dollar liquidity utilizing an augmented swap arrangement with the U.S. Federal Reserve. This initiative helped the dollar funding of Japanese banks, providing close to $200 billion.

Despite many ensuing waves of infection, the world’s financial system stayed stable and continue to support the real economy. The overwhelming firepower employed by the U.S. Federal Reserve must have underpinned this. If the Fed had been too little, too late in March 2020, the world would have looked utterly different from what we see today.

The debate on the lessons from the March 2020 market turmoil continues. During the incident, banks largely functioned without major problems, and the debate focused on issues surrounding investment funds including money market funds and capital markets including U.S. treasuries and the commercial paper markets.

On the one hand, many central bankers argue that the exceptional responses in March should not be repeated and that globally uniform regulations should be imposed on the nonbank financial sector, which now holds half of the world’s financial assets, lest similar funding problems should recur.

On the other hand, many capital market regulators maintain that it is the role of central banks to mitigate extreme tail events and that if you demand that market participants to be prepared for any exceptional development, the market in peacetime would be stifled.

The debate continues, but remedial measures are being developed. The FSB published a comprehensive work program5 and specific proposals. Even the most specific proposal, or that on Money Market Fund (MMF),6 however, entails significant range of national discretion, and we need to see the outcome of the peer review planned in 2023 to ascertain the effectiveness of the reform. Studies on the way to enhance the resilience of other nonbank sectors have also begun, but it would take several more years before remedies are agreed and implemented.

The vulnerabilities of the nonbank financial sector were among the key factors exacerbating the GFC. The views did not converge enough between central bankers and capital market regulators in the wake of that crisis either, and the agreed remedial measures were perhaps not effective enough. It may be said that the incomplete homework from the GFC led to the March 2020 turmoil.

Following the GFC, authorities tightened banking regulations and eased monetary policy. Though the tightened banking regulation contributed to the banks’ resilience against the COVID‑19 shock, it could also be said that the combination of tight banking regulation and easy monetary policy helped nonbank financial sector’s inordinate growth and thus exacerbated the March dash for cash.

In July 2021, the U.S. Federal Reserve reintroduced the repo facilities for domestic market participants and for foreign and international monetary authorities adopted in March 2020. This may have been intended as a cautionary measure to prevent market turbulences while unwinding the extraordinary liquidity provision since March 2020.

In November 2021, the Fed began to taper the monthly asset purchase amount. A decline in market liquidity was observed since then for Treasury bonds and stock and oil futures.7 Quantitative tightening started in June 2022.

The processes to address the legacies of the March 2020 market turbulence are far from complete despite more than two years passing since the incident.

4 For more detailed descriptions, see Financial Stability Board, Holistic Review of the March Market Turmoil, November 2020.

5 “Table 1: Planned deliverables under the FSB’s NBFI Work Programme” of Financial Stability Board, Enhancing the Resilience of Non-Bank Financial Intermediation: Progress report, November 2021.

6 Financial Stability Board, Policy proposals to enhance money market fund resilience: Final report, October 2021

7 See Box 1.1. Recent Liquidity Strains across U.S. Treasury, Equity Index Futures, and Oil Futures Markets, of Board of Governors of Federal Reserve System, Financial Stability Report, May 2022

(2022年07月01日「基礎研レポート」)

氷見野 良三

氷見野 良三のレポート

| 日付 | タイトル | 執筆者 | 媒体 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022/12/07 | データからナラティブへ-非財務情報の開示のあり方を巡って | 氷見野 良三 | 基礎研マンスリー |

| 2022/10/14 | データからナラティブへ-非財務情報の開示のあり方を巡って | 氷見野 良三 | 基礎研レポート |

| 2022/08/05 | ロシアのウクライナ侵略は「グローバル化の終わり」を告げるのか | 氷見野 良三 | 基礎研マンスリー |

| 2022/07/01 | Reflections on Financial Regulators’ Initial Responses to COVID-19 | 氷見野 良三 | 基礎研レポート |

新着記事

-

2025年10月21日

今週のレポート・コラムまとめ【10/14-10/20発行分】 -

2025年10月20日

中国の不動産関連統計(25年9月)~販売は前年減が続く -

2025年10月20日

ブルーファイナンスの課題-気候変動より低い関心が普及を阻む -

2025年10月20日

家計消費の動向(単身世帯:~2025年8月)-外食抑制と娯楽維持、単身世帯でも「メリハリ消費」の傾向 -

2025年10月20日

縮小を続ける夫婦の年齢差-平均3歳差は「第二次世界大戦直後」という事実

レポート紹介

-

研究領域

-

経済

-

金融・為替

-

資産運用・資産形成

-

年金

-

社会保障制度

-

保険

-

不動産

-

経営・ビジネス

-

暮らし

-

ジェロントロジー(高齢社会総合研究)

-

医療・介護・健康・ヘルスケア

-

政策提言

-

-

注目テーマ・キーワード

-

統計・指標・重要イベント

-

媒体

- アクセスランキング

お知らせ

-

2025年07月01日

News Release

-

2025年06月06日

News Release

-

2025年04月02日

News Release

【Reflections on Financial Regulators’ Initial Responses to COVID-19】【シンクタンク】ニッセイ基礎研究所は、保険・年金・社会保障、経済・金融・不動産、暮らし・高齢社会、経営・ビジネスなどの各専門領域の研究員を抱え、様々な情報提供を行っています。

Reflections on Financial Regulators’ Initial Responses to COVID-19のレポート Topへ

各種レポート配信をメールでお知らせ。読み逃しを防ぎます!

各種レポート配信をメールでお知らせ。読み逃しを防ぎます!