- NLI Research Institute >

- Financial and foreign exchange >

- Reflections on Financial Regulators’ Initial Responses to COVID-19

18/05/2022

Reflections on Financial Regulators’ Initial Responses to COVID-19

Policy Research Department Ryozo Himino

Font size

- S

- M

- L

4――Responses to prevent a credit crunch and to address solvency risks

After the March 2020 liquidity risk incident, many regulators recalled past crises where liquidity risk phases were followed by solvency risk phases. The infection and lockdown put a brake on supply and demand, and the corporate and household sectors lost revenues. If the pandemic continues, banks’ loans to them may stop performing, causing credit losses on banks.

On the other hand, if banks, being wary of creating bad loans, take back the umbrella on rainy days and cause credit crunch, firms which can resurrect after the pandemic will unnecessarily go bankrupt. Households, which can start to repay the mortgage after the pandemic, may have to sell their houses.

There are both interdependency and trade-offs between the financial stability and the continued availability of financing.

The financial stability and the availability of financing are interdependent. If the credit crunch exacerbates the recession, the recession increases bad loans and destabilize the financial system, and impaired financial stability worsen the credit crunch. Unless we both have financial stability and financing, we cannot have even one of the two.

There are, however, tradeoffs between the financial stability and financing as well. If another wave of the pandemic further deepens the recession after banks abundantly provide bridge financing, big bad loans may be created and impair financial stability. If banks prioritize not running the risk of creating bad loans, firms and households cannot get bridge financing.

In addition to this coexistence of interdependency and tradeoffs, the following factors further complicated the matter.

First, the fallacy of composition. A policy rational to an individual bank may not be rational for the financial system as a whole or for the economy overall.

A bank that unduly turns its back on customers in need will not be trusted and will lose businesses in the longer term, and banks with enough financial clout will continue to support viable customers.

But those banks without enough capital will have to prioritize minimizing immediate credit losses. As actions by an individual bank alone cannot sustain the whole economy, it may refrain from lending to customers without existing relationship or with higher risks. If each bank makes such choices, the recession will become deep, and all banks may have to bear large credit losses.

Second, uncertainty about the COVID‑19. The amount of losses a firm or a household will accumulate depends on the duration of the pandemic, its impact on the economy, and the government support to the firms, households, and economy. The banks had to make lending decision without knowing these factors.

Third, uncertainty about the post-COVID‑19 era. After the pandemic, will people continue to use Zoom for meetings or resume business trips? Will tourist from abroad start sightseeing? Will there be big parties and wedding ceremonies? Will the borrower firm be capable to seize new business opportunities? A bank cannot determine if the bridge financing will lead to the other shore without knowing the answers to these questions, which nobody knows.

Facing these complications, financial regulators took policy measures to ensure both the financial stability and the availability of financing.

The JFSA had maintained since several years before the pandemic that its mission was to realize both financial stability and effective financial intermediation.8 This had been an outlier view as many regulators around the world considered their unique mission was securing financial stability. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, however, most regulators worked to secure effective financial intermediation as well.

Specifically, regulators adopted the following measures:

The Accounting Standard Board of Japan (ASBJ) announced that deviation between the ex-ante best estimation and the ex-post outcome should not constitute an error unless the assumptions adopted by the reporting entities are clearly unreasonable. The JFSA announced that it would respect judgements by banks when conducting on-site inspections.

To secure financial stability, regulators took the following measures:

Other authorities, which used to deny the use of public funds, started to show nuanced changes. For example, a report by the FSB in March 2021 stated:

The sentences could be interpreted to implicitly accept that the bail-in options introduced post-GFC are not necessarily the only available options.

The regulatory responses described above should have contributed to financial stability and the prevention of a credit crunch. Their effectiveness, however, had certain limitations. For example, banks globally continued to hesitate to use buffers despite encouragement from regulators. U.S. banks posted enormous loan loss reserves despite the clarifications offered by accounting standard bodies and regulators.

The financial system maintained its stability and continued to support the economy perhaps due to the combined effects of (1) the regulatory responses listed above, (2) fiscal policy, (3) monetary policy, and (4) post-GFC regulatory reforms. Most likely, all the four were indispensable.

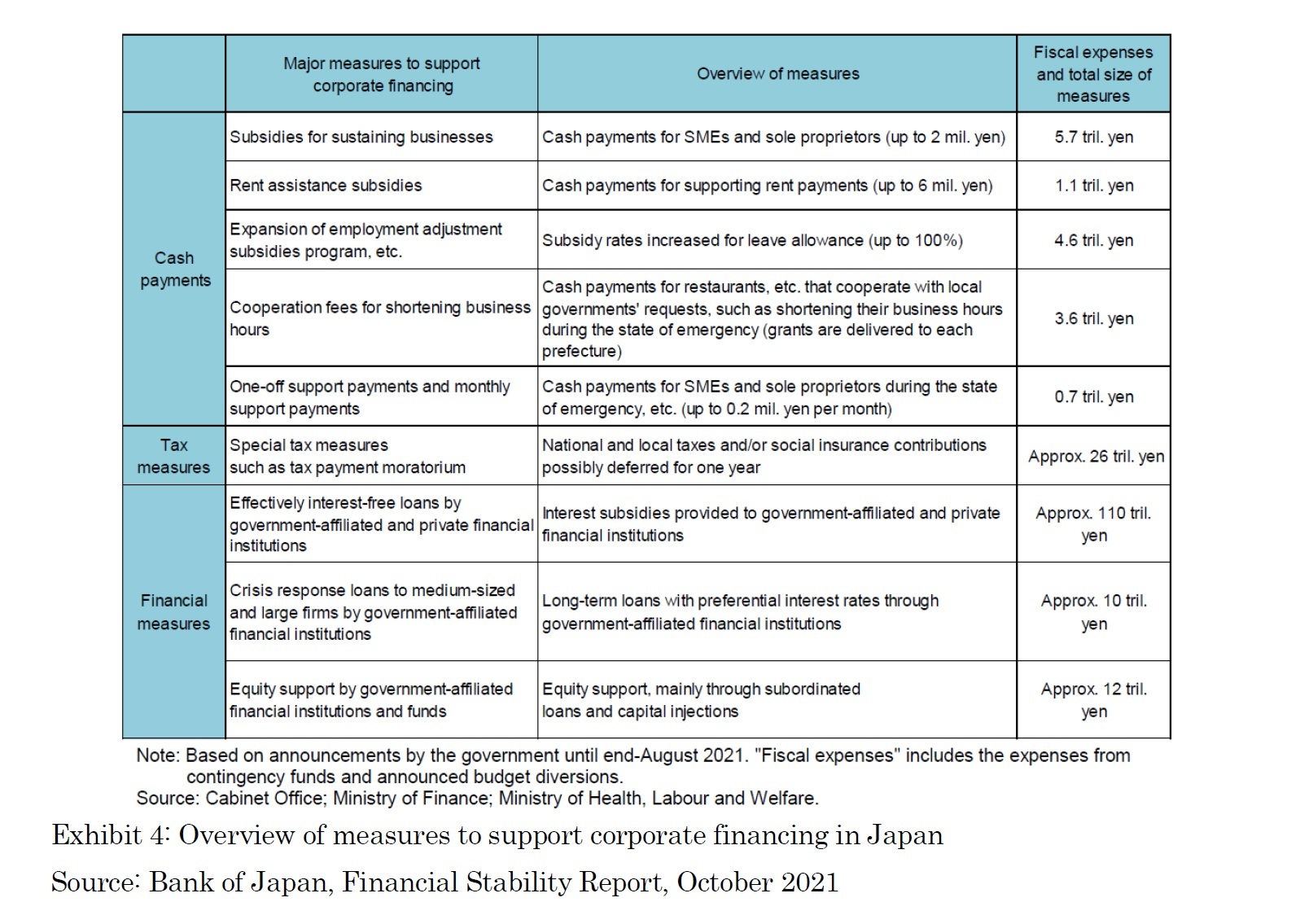

The fiscal policy pursued provided grants and subsidies to households and corporations, compensating for the loss of revenue and alleviating the deterioration of balance sheets. Public guarantees made it possible for banks to lend without fearing future credit losses. Exhibit 4 shows the variety and expanse of the measures taken to support corporate borrowers in Japan.

On the other hand, if banks, being wary of creating bad loans, take back the umbrella on rainy days and cause credit crunch, firms which can resurrect after the pandemic will unnecessarily go bankrupt. Households, which can start to repay the mortgage after the pandemic, may have to sell their houses.

There are both interdependency and trade-offs between the financial stability and the continued availability of financing.

The financial stability and the availability of financing are interdependent. If the credit crunch exacerbates the recession, the recession increases bad loans and destabilize the financial system, and impaired financial stability worsen the credit crunch. Unless we both have financial stability and financing, we cannot have even one of the two.

There are, however, tradeoffs between the financial stability and financing as well. If another wave of the pandemic further deepens the recession after banks abundantly provide bridge financing, big bad loans may be created and impair financial stability. If banks prioritize not running the risk of creating bad loans, firms and households cannot get bridge financing.

In addition to this coexistence of interdependency and tradeoffs, the following factors further complicated the matter.

First, the fallacy of composition. A policy rational to an individual bank may not be rational for the financial system as a whole or for the economy overall.

A bank that unduly turns its back on customers in need will not be trusted and will lose businesses in the longer term, and banks with enough financial clout will continue to support viable customers.

But those banks without enough capital will have to prioritize minimizing immediate credit losses. As actions by an individual bank alone cannot sustain the whole economy, it may refrain from lending to customers without existing relationship or with higher risks. If each bank makes such choices, the recession will become deep, and all banks may have to bear large credit losses.

Second, uncertainty about the COVID‑19. The amount of losses a firm or a household will accumulate depends on the duration of the pandemic, its impact on the economy, and the government support to the firms, households, and economy. The banks had to make lending decision without knowing these factors.

Third, uncertainty about the post-COVID‑19 era. After the pandemic, will people continue to use Zoom for meetings or resume business trips? Will tourist from abroad start sightseeing? Will there be big parties and wedding ceremonies? Will the borrower firm be capable to seize new business opportunities? A bank cannot determine if the bridge financing will lead to the other shore without knowing the answers to these questions, which nobody knows.

Facing these complications, financial regulators took policy measures to ensure both the financial stability and the availability of financing.

The JFSA had maintained since several years before the pandemic that its mission was to realize both financial stability and effective financial intermediation.8 This had been an outlier view as many regulators around the world considered their unique mission was securing financial stability. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, however, most regulators worked to secure effective financial intermediation as well.

Specifically, regulators adopted the following measures:

- Release of the countercyclical buffer

Basel III, the international standards on bank capital adequacy, incorporates the framework of the counter-cyclical buffer, in which regulators discretionally set add-on to capital requirement in view of the changing business conditions. European and other authorities, who had set add-ons before the pandemic, released them. Japanese and U.S. authorities had not established add-ons and therefore had no room for releasing buffers.

- Encouragement to use other buffers

Basel III framework incorporates standing buffers in addition to the releasable counter-cyclical one. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and national authorities including the JFSA confirmed that the buffers exist to be used in times of need such as the current pandemic and attempted to alleviate banks’ concerns about dipping into buffers.

- Clarification on loan loss reserves

As part of the post-GFC reforms, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and U.S. accounting standards have come to request that loan loss provisions be set in a forward-looking manner. Accounting standard setters clarified that the requirement should not be implemented mechanically given the difficulty in foreseeing the impacts of COVID‑19.

The Accounting Standard Board of Japan (ASBJ) announced that deviation between the ex-ante best estimation and the ex-post outcome should not constitute an error unless the assumptions adopted by the reporting entities are clearly unreasonable. The JFSA announced that it would respect judgements by banks when conducting on-site inspections.

- Encouragement to accommodate funding needs

Authorities encouraged banks to accommodate funding needs. In Japan, the Minister for Financial Services released statements thirteen times on the occasion of the declarations of emergency and other occasions. The JFSA continuously surveyed borrowers’ views and requested banks to address identified problems. The requests were issued 34 times.

- Moratorium

Many jurisdictions took various forms of measures to allow repayment deferrals. Germany and other jurisdictions temporarily terminated filing of bankruptcy. On March 6, 2020, the JFSA requested financial institutions to respond to borrowers’ request to change lending terms including payment deferrals in a prompt and flexible manner and announced that it would publish the percentage of the requests accommodated. Almost all requests have been accommodated.

To secure financial stability, regulators took the following measures:

- Restraining dividends and share buybacks

European authorities requested banks to stop dividend payouts and share buybacks. U.S. authorities set limits on capital disbursements according to the outcome of stress tests. The JFSA had a dialogue with individual banks according to their specific conditions.

- Stress tests

UK authorities published the outcome of stress tests confirming that increased lending or pandemic-induced bad loans would not endanger financial stability. The outcome justified the regulator’s encouragement to continue lending.

- Public support to banks

Japan amended the Act on Special Measures for Strengthening Financial Functions in June 2020 to allow public fund injections to financial institutions needing to enhance their capital adequacy to continue to support the economy.

Other authorities, which used to deny the use of public funds, started to show nuanced changes. For example, a report by the FSB in March 2021 stated:

[S]ignificant progress has been made since the global financial crisis in establishing and operationalizing frameworks for the resolution of systemically important banks. These reforms give authorities more options for dealing with banks in distress, though which options are used is for authorities to consider in their particular circumstances.9

The sentences could be interpreted to implicitly accept that the bail-in options introduced post-GFC are not necessarily the only available options.

The regulatory responses described above should have contributed to financial stability and the prevention of a credit crunch. Their effectiveness, however, had certain limitations. For example, banks globally continued to hesitate to use buffers despite encouragement from regulators. U.S. banks posted enormous loan loss reserves despite the clarifications offered by accounting standard bodies and regulators.

The financial system maintained its stability and continued to support the economy perhaps due to the combined effects of (1) the regulatory responses listed above, (2) fiscal policy, (3) monetary policy, and (4) post-GFC regulatory reforms. Most likely, all the four were indispensable.

The fiscal policy pursued provided grants and subsidies to households and corporations, compensating for the loss of revenue and alleviating the deterioration of balance sheets. Public guarantees made it possible for banks to lend without fearing future credit losses. Exhibit 4 shows the variety and expanse of the measures taken to support corporate borrowers in Japan.

Monetary policy in countries with room to reduce policy rates moved to alleviate the interest-payment burden on corporations and households. Central banks adopted programs to purchase large amounts of assets with credit risk and long maturities and to support banks’ lending to borrowers in need.

In addition, post-GFC regulatory reforms ensured banks’ strong balance sheets, which enabled banks to support the economy while maintaining soundness.

A devastating solvency risk phase did not materialize, which regulators had initially feared seeing following the March 2020 liquidity risk phase. In addition to the four factors above, quick recovery in the manufacturing sector contributed to this outcome.

As Exhibit 1 demonstrates, we observed a K-shaped recovery, where all industries initially recorded a crash, and then some industries recovered while others stagnated. This is of course much worse than a V-shaped recovery, but better than an L-shaped recovery.

The corporate sector in Japan entered the pandemic era with a solid balance sheet, after retaining earnings and hoarding cash for decades, but pre-pandemic U.S. corporations were seen to have accumulated excessive debts. Some feared that the vulnerabilities might be exposed by the COVID‑19 shock. Indeed, the default rate of U.S. high-yield bonds increased from pre-pandemic level of less than 3% to around 7% in the middle of 2020. Though rating agencies anticipated a further rise, however, the default rate then stabilized and returned to the pre-pandemic level by mid-2021. The default rate of European non-investment grade bonds showed a similar trajectory.

In November 2021, the U.S. Federal Reserve stated that the vulnerabilities arising from business debt returned to the pre-pandemic level.10 Continued recovery of earnings, the low level of interest rates, support from the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), and fiscal stimulus contributed. Household vulnerabilities also returned to the pre-pandemic level. A combination of extensions in borrower relief programs, fiscal stimulus, and high personal savings rates have helped the recovery of household balance sheets.

In the same month, the European Central Bank also stated that corporate debt-servicing capacity improved due to low financing costs, increased revenues, and continued public support measures, and that near-term euro area corporate insolvency concerns fell.11

For a definitive conclusion, it is necessary to see what impacts could arise from lifting the support measures and rising policy rates going forward. It is already evident, however, that the combination of regulatory, fiscal, and monetary responses has been highly effective in addressing the concern about financial stability and securing continued financial support for the economy.

8 See, for example, Ryozo Himino, Replacing checklists with engagement, March 2018

9 Financial Stability Board, Evaluation of the Effects of Too-Big-To-Fail Reforms: Final Report, April 2021

10 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Financial Stability Report, November 2021

11 European Central Bank, Financial Stability Review, November 2021

In addition, post-GFC regulatory reforms ensured banks’ strong balance sheets, which enabled banks to support the economy while maintaining soundness.

A devastating solvency risk phase did not materialize, which regulators had initially feared seeing following the March 2020 liquidity risk phase. In addition to the four factors above, quick recovery in the manufacturing sector contributed to this outcome.

As Exhibit 1 demonstrates, we observed a K-shaped recovery, where all industries initially recorded a crash, and then some industries recovered while others stagnated. This is of course much worse than a V-shaped recovery, but better than an L-shaped recovery.

The corporate sector in Japan entered the pandemic era with a solid balance sheet, after retaining earnings and hoarding cash for decades, but pre-pandemic U.S. corporations were seen to have accumulated excessive debts. Some feared that the vulnerabilities might be exposed by the COVID‑19 shock. Indeed, the default rate of U.S. high-yield bonds increased from pre-pandemic level of less than 3% to around 7% in the middle of 2020. Though rating agencies anticipated a further rise, however, the default rate then stabilized and returned to the pre-pandemic level by mid-2021. The default rate of European non-investment grade bonds showed a similar trajectory.

In November 2021, the U.S. Federal Reserve stated that the vulnerabilities arising from business debt returned to the pre-pandemic level.10 Continued recovery of earnings, the low level of interest rates, support from the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), and fiscal stimulus contributed. Household vulnerabilities also returned to the pre-pandemic level. A combination of extensions in borrower relief programs, fiscal stimulus, and high personal savings rates have helped the recovery of household balance sheets.

In the same month, the European Central Bank also stated that corporate debt-servicing capacity improved due to low financing costs, increased revenues, and continued public support measures, and that near-term euro area corporate insolvency concerns fell.11

For a definitive conclusion, it is necessary to see what impacts could arise from lifting the support measures and rising policy rates going forward. It is already evident, however, that the combination of regulatory, fiscal, and monetary responses has been highly effective in addressing the concern about financial stability and securing continued financial support for the economy.

8 See, for example, Ryozo Himino, Replacing checklists with engagement, March 2018

9 Financial Stability Board, Evaluation of the Effects of Too-Big-To-Fail Reforms: Final Report, April 2021

10 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Financial Stability Report, November 2021

11 European Central Bank, Financial Stability Review, November 2021