- シンクタンクならニッセイ基礎研究所 >

- 経済 >

- 経済予測・経済見通し >

- Japan’s Economic Outlook for FY 2020–2022

2021年02月25日

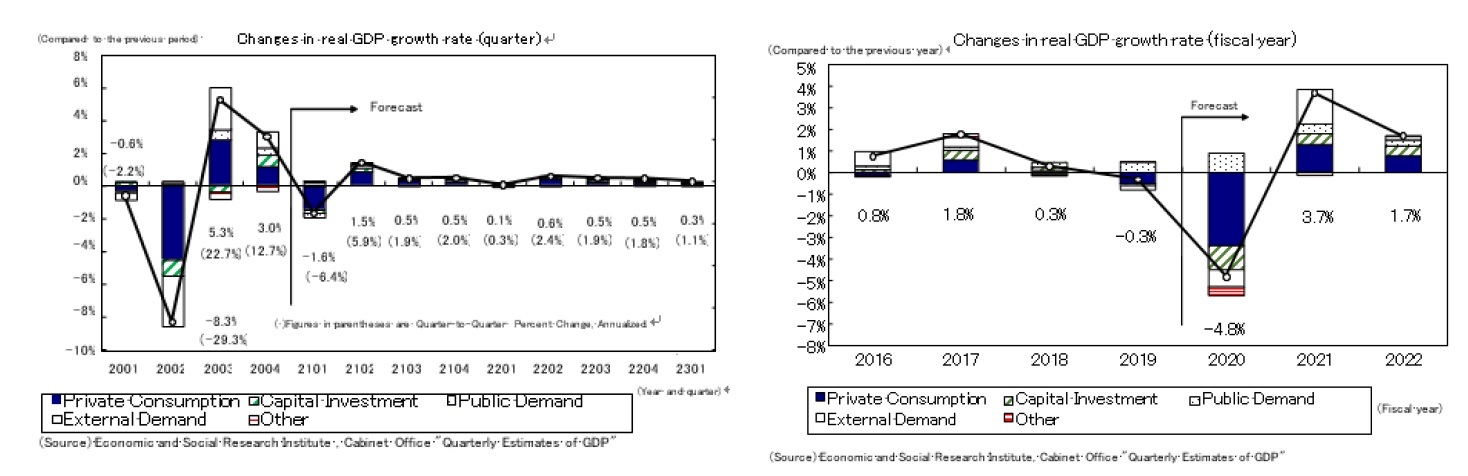

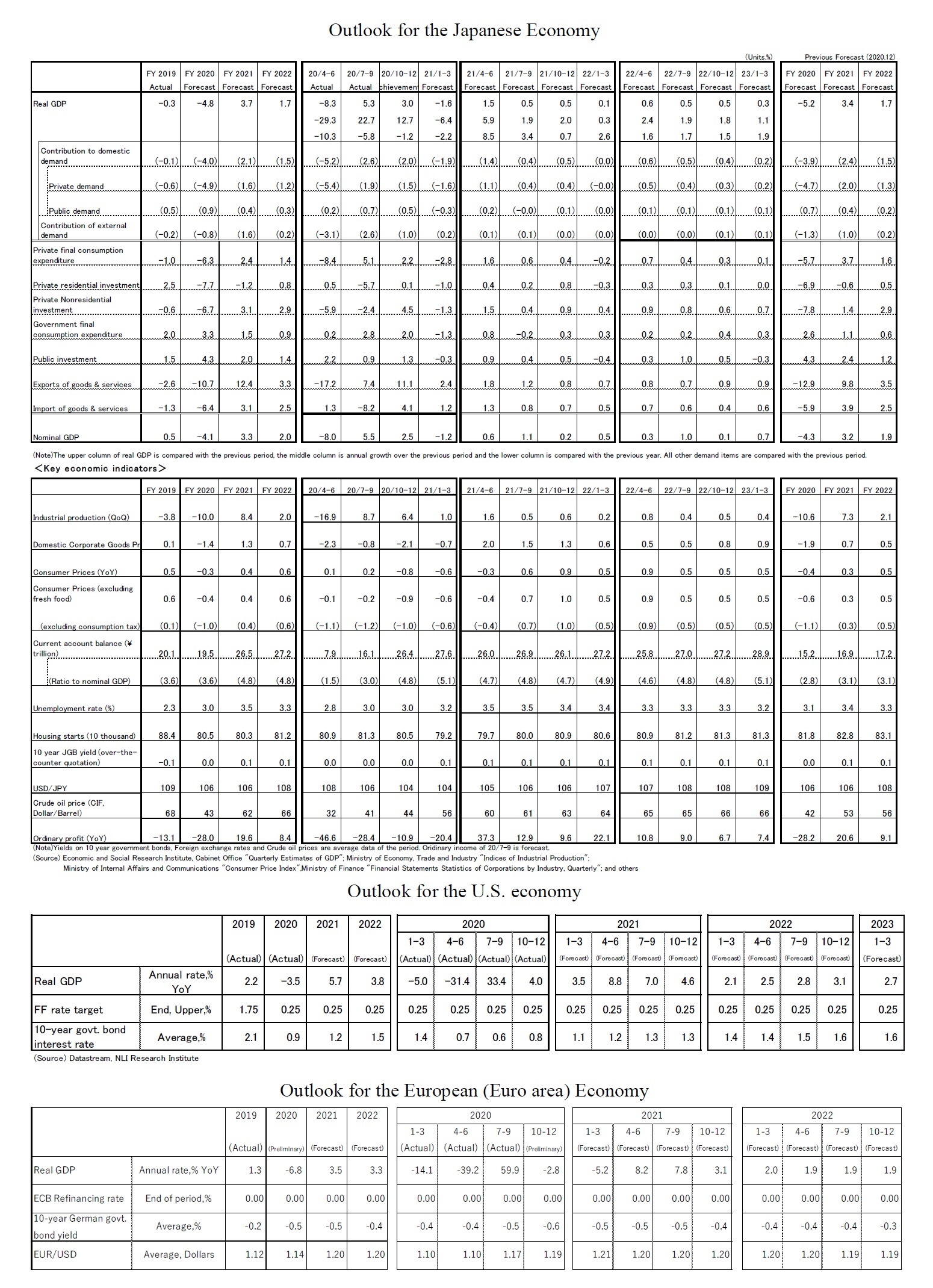

2. The real growth rate is expected to be -4.8% in FY 2020, 3.7% in FY 2021 and 1.7% in FY 2022.

Real GDP will exceed its most recent peak in FY 2023

In 2020, the Japanese economy declined rapidly in the first half of the year due to calls for self-restraint in response to the spread of the new coronavirus infection and the declaration of a state of emergency (January–March: down 2.2% annualized compared to the previous quarter; April–June: down 29.3%). However, economic activities resumed following the lifting of the state of emergency, and the economy recovered in the second half at a faster pace than expected (July–September quarter: 22.7%; October–December quarter: 12.7%).

The economy, however, is likely to post negative growth in the first quarter of 2021, as the state of emergency has been re-declared. Previously, restaurants, amusement facilities, and department stores were forced to close down, but this time the scope of regulations is narrow, such as shortening restaurant business hours and limiting the number of large-scale events. In the previous state of emergency, the target area was initially limited to seven prefectures but was later expanded to the whole country. Currently, the state of emergency is limited to 11 prefectures (from January 8–13: four prefectures; from February 8 onward: 10 prefectures). Furthermore, before a state of emergency was re-declared, consumption was already at a lower level than normal. Given these factors, it is highly likely that the negative impacts on personal consumption will be smaller than during the previous state of emergency.

However, the economy has lost much of its endurance even if limits on economic activities are less severe than they were at the time of the declaration of the state of emergency. For example, ordinary income fell more than 20% below pre-coronavirus levels. In particular, the hotel and restaurant industries, which were strongly affected by the new coronavirus, posted losses for three consecutive quarters from the first quarter of 2020. In addition, earned surplus (so-called internal reserves), which had been increasing substantially, declined in the April–June and July–September quarters of 2020 due to a sharp decline in corporate earnings. In particular, the earned surplus of the lodging industry and the food and drink service industry declined by half from the previous year, and the actual amount of earned surplus of SMEs with capital of 10–20 million yen was negative. Although the impact of the state of emergency itself is small, the risk of companies closing down or going bankrupt has increased rapidly. Additionally, the risk of rising unemployment has spiked, and is higher than at the time of the previous state of emergency last year.

In the January–March quarter of 2021, the real GDP growth rate is expected to drop 1.6% (down 6.4% per annum) from the previous quarter, the first negative growth in three quarters. Private consumption is likely to drop 2.8% from the previous quarter for the first time in three quarters, and capital investment is likely to drop 1.3%.

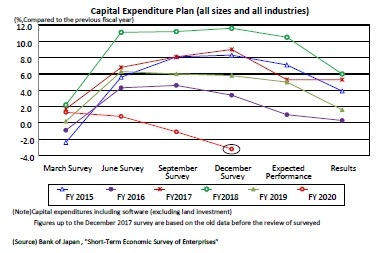

In the October–December 2020 quarter, capital investment increased, reflecting a recovery in exports and production and a halt to deteriorating corporate earnings. According to the Tankan December 2020 survey, however, the capital investment plan for fiscal 2020 (including software and R&D investments and excluding land investments) was revised downward by 2.1% from the September 2020 survey, and was 3.0% (all sizes and all industries) down from the previous year.

Capital investment is expected to weaken again in 2021 as economic activity once more declines. Although corporate earnings have recovered, they remain at low levels. Indeed, the assumption of ample cash flows that can support strong capital investments has collapsed. In addition, machinery investment in the manufacturing sector is expected to remain firm as production activity recovers, while construction investment in the non-manufacturing sector, including the restaurant and accommodation industries, is expected to remain sluggish. It is highly likely that it will take some time for capital investment to recover as a whole.

In 2020, the Japanese economy declined rapidly in the first half of the year due to calls for self-restraint in response to the spread of the new coronavirus infection and the declaration of a state of emergency (January–March: down 2.2% annualized compared to the previous quarter; April–June: down 29.3%). However, economic activities resumed following the lifting of the state of emergency, and the economy recovered in the second half at a faster pace than expected (July–September quarter: 22.7%; October–December quarter: 12.7%).

The economy, however, is likely to post negative growth in the first quarter of 2021, as the state of emergency has been re-declared. Previously, restaurants, amusement facilities, and department stores were forced to close down, but this time the scope of regulations is narrow, such as shortening restaurant business hours and limiting the number of large-scale events. In the previous state of emergency, the target area was initially limited to seven prefectures but was later expanded to the whole country. Currently, the state of emergency is limited to 11 prefectures (from January 8–13: four prefectures; from February 8 onward: 10 prefectures). Furthermore, before a state of emergency was re-declared, consumption was already at a lower level than normal. Given these factors, it is highly likely that the negative impacts on personal consumption will be smaller than during the previous state of emergency.

However, the economy has lost much of its endurance even if limits on economic activities are less severe than they were at the time of the declaration of the state of emergency. For example, ordinary income fell more than 20% below pre-coronavirus levels. In particular, the hotel and restaurant industries, which were strongly affected by the new coronavirus, posted losses for three consecutive quarters from the first quarter of 2020. In addition, earned surplus (so-called internal reserves), which had been increasing substantially, declined in the April–June and July–September quarters of 2020 due to a sharp decline in corporate earnings. In particular, the earned surplus of the lodging industry and the food and drink service industry declined by half from the previous year, and the actual amount of earned surplus of SMEs with capital of 10–20 million yen was negative. Although the impact of the state of emergency itself is small, the risk of companies closing down or going bankrupt has increased rapidly. Additionally, the risk of rising unemployment has spiked, and is higher than at the time of the previous state of emergency last year.

In the January–March quarter of 2021, the real GDP growth rate is expected to drop 1.6% (down 6.4% per annum) from the previous quarter, the first negative growth in three quarters. Private consumption is likely to drop 2.8% from the previous quarter for the first time in three quarters, and capital investment is likely to drop 1.3%.

In the October–December 2020 quarter, capital investment increased, reflecting a recovery in exports and production and a halt to deteriorating corporate earnings. According to the Tankan December 2020 survey, however, the capital investment plan for fiscal 2020 (including software and R&D investments and excluding land investments) was revised downward by 2.1% from the September 2020 survey, and was 3.0% (all sizes and all industries) down from the previous year.

Capital investment is expected to weaken again in 2021 as economic activity once more declines. Although corporate earnings have recovered, they remain at low levels. Indeed, the assumption of ample cash flows that can support strong capital investments has collapsed. In addition, machinery investment in the manufacturing sector is expected to remain firm as production activity recovers, while construction investment in the non-manufacturing sector, including the restaurant and accommodation industries, is expected to remain sluggish. It is highly likely that it will take some time for capital investment to recover as a whole.

While the first quarter will see negative growth, the drop is likely to be much smaller than it was at the time of the previous state of emergency. The decline in private consumption was only about a third of the level of the previous state of emergency (April–June 2020: down 8.4% compared to the previous quarter; January–March 2021: down 2.8%), and that external demand, which significantly pushed down the growth rate in the April–June quarter of 2020, was the driving force behind the growth rate.

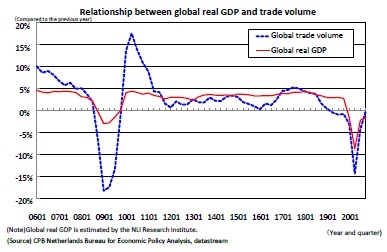

While the first quarter will see negative growth, the drop is likely to be much smaller than it was at the time of the previous state of emergency. The decline in private consumption was only about a third of the level of the previous state of emergency (April–June 2020: down 8.4% compared to the previous quarter; January–March 2021: down 2.8%), and that external demand, which significantly pushed down the growth rate in the April–June quarter of 2020, was the driving force behind the growth rate.Since the winter of 2020, moves to restrict economic activities have again been spreading in Europe and the United States. The service industry has been strongly affected by this trend, with an increase in pent-up demand and stay-at-home consumption leading to steady consumption of goods on the whole. Moreover, production activities in the manufacturing industry have been robust. The situation is quite different from the spring of 2020, when imports and exports dropped sharply due to the shutdown of factories in many countries.

According to the CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, the spring 2020 volume of world trade declined by about 15% from the previous year, exceeding the real GDP decline. By the end of 2020, however, trade volume recovered rapidly to the level of the previous year due to strong global production activity. Japanese exports to Europe—where negative growth is expected in the January-March quarter of 2021as well as the October–December quarter of 2020 —are expected to remain weak. Overall exports, however, are expected to remain strong as exports to the United States and China remain robust.

On the premise that the state of emergency will be lifted, the economy is expected to grow in the April–June quarter of 2021 at an annual rate of 5.9% from the previous quarter. Continued growth is then expected at a rate clearly higher than the potential growth rate as the economy is in the process of normalization. However, it will take time for economic activity to return to the pre-coronavirus level. Even if a state of emergency is lifted, social distancing from the pandemic will continue to restrain the consumption of face-to-face services while deteriorating corporate earnings and lowering employment and income, which exerts downward pressure on future demand. In addition, a decline in supply capacity caused by the pandemic may slow the recovery of future demand in industries where demand has remained largely depressed. For example, in the accommodation industry, which has been strongly affected by the loss of inbound demand, the number of guest rooms required to accommodate foreign visitors has declined significantly due to a series of bankruptcies and the downsizing of businesses. These effects are likely to exert downward pressure on demand in the medium to long term.

On the premise that the state of emergency will be lifted, the economy is expected to grow in the April–June quarter of 2021 at an annual rate of 5.9% from the previous quarter. Continued growth is then expected at a rate clearly higher than the potential growth rate as the economy is in the process of normalization. However, it will take time for economic activity to return to the pre-coronavirus level. Even if a state of emergency is lifted, social distancing from the pandemic will continue to restrain the consumption of face-to-face services while deteriorating corporate earnings and lowering employment and income, which exerts downward pressure on future demand. In addition, a decline in supply capacity caused by the pandemic may slow the recovery of future demand in industries where demand has remained largely depressed. For example, in the accommodation industry, which has been strongly affected by the loss of inbound demand, the number of guest rooms required to accommodate foreign visitors has declined significantly due to a series of bankruptcies and the downsizing of businesses. These effects are likely to exert downward pressure on demand in the medium to long term.Furthermore, it is expected that the number of coronavirus infections will decrease to a certain extent from April 2021 due to the spread of vaccines. However, it is unlikely that the number of infected people will drop to zero, and it is inevitable that the number of cases will increase in winter when the virus becomes active and immune systems deteriorate due to falling temperatures. In such cases, public health measures aimed at preventing the spread of the disease may stagnate economic activity, particularly personal consumption.

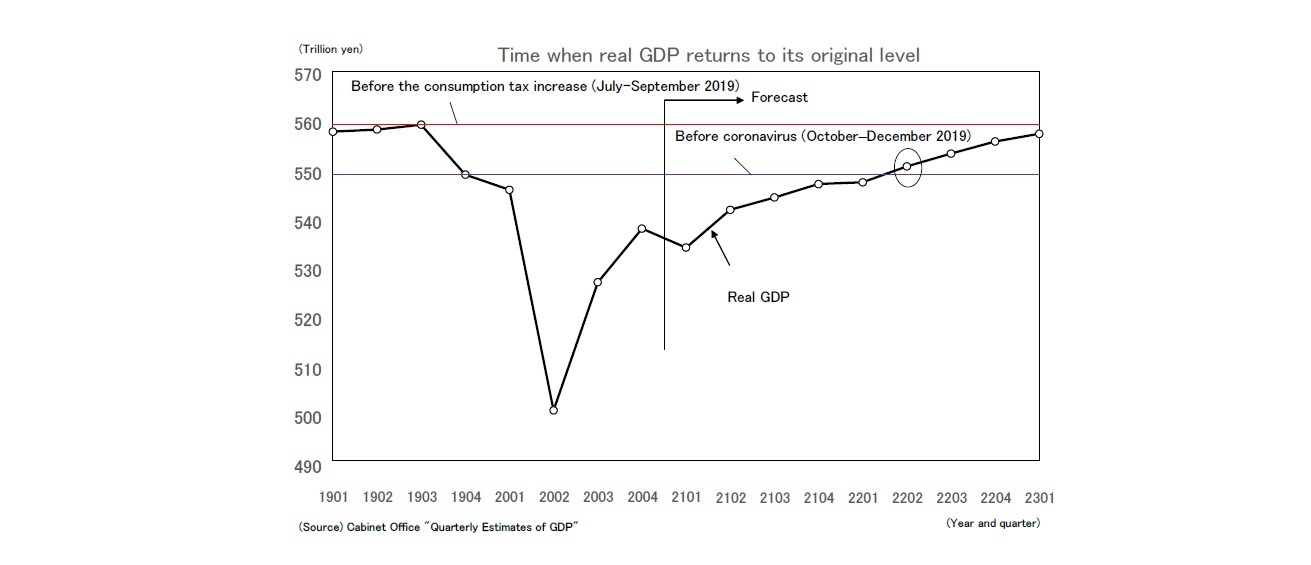

The real GDP growth rate is forecast to be −4.8% in fiscal 2020, 3.7% in fiscal 2021, and 1.7% in fiscal 2022. Real GDP will exceed pre-coronavirus (October–December quarter of 2019) levels in the April–June quarter of 2022, but will not return to its most recent peak (occurring before the consumption tax increase in July–September quarter of 2019) until 2023.

Consumer price outlook

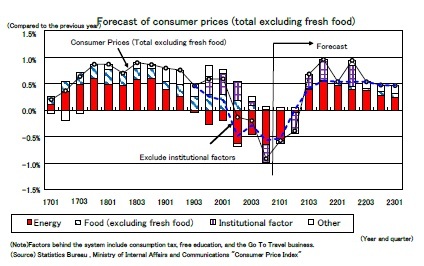

In December 2020, the Consumer Price Index (total excluding fresh food, or core CPI) declined 1.0% from the previous year, falling for the first time in 10 years more than 1%. The main reasons for this decline were a fall in energy prices due to a decline in crude oil prices and a sharp drop in accommodation charges due to the Go To Travel campaign. Excluding these two factors, the core CPI growth rate was almost 0%, and the underlying trend in prices has not weakened despite the sharp decline in economic activity. Prices may have remained bouyant because the consumption of goods such as foods, daily necessities, and home electric appliances has been steady due to the expansion in stay-at-home consumption. Unlike an ordinary economic downturn, it is not possible to expect current demand to be stimulated by price reductions for services such as dining out, for which demand has declined sharply due to requests for self-restraint.

In December 2020, the Consumer Price Index (total excluding fresh food, or core CPI) declined 1.0% from the previous year, falling for the first time in 10 years more than 1%. The main reasons for this decline were a fall in energy prices due to a decline in crude oil prices and a sharp drop in accommodation charges due to the Go To Travel campaign. Excluding these two factors, the core CPI growth rate was almost 0%, and the underlying trend in prices has not weakened despite the sharp decline in economic activity. Prices may have remained bouyant because the consumption of goods such as foods, daily necessities, and home electric appliances has been steady due to the expansion in stay-at-home consumption. Unlike an ordinary economic downturn, it is not possible to expect current demand to be stimulated by price reductions for services such as dining out, for which demand has declined sharply due to requests for self-restraint.

As for the outlook, the rate of decline in energy prices is expected to become smaller and turn positive in summer as a result of the recent sharp rise in crude oil prices. Also, since Go To Travel has been halted since December 28, the rate of increase in the core CPI since January 2021 will be pushed up by around 0.4% due to a smaller drop in accommodation prices. We expect Go To Travel to resume in April after the state of emergency is lifted and finish at the end of June. As a result, the rate of increase in the core CPI in the April–June quarter of 2021 will again decline by about 0.4%. In the same quarter of 2022, it will be pushed up by the same amount.

As for the outlook, the rate of decline in energy prices is expected to become smaller and turn positive in summer as a result of the recent sharp rise in crude oil prices. Also, since Go To Travel has been halted since December 28, the rate of increase in the core CPI since January 2021 will be pushed up by around 0.4% due to a smaller drop in accommodation prices. We expect Go To Travel to resume in April after the state of emergency is lifted and finish at the end of June. As a result, the rate of increase in the core CPI in the April–June quarter of 2021 will again decline by about 0.4%. In the same quarter of 2022, it will be pushed up by the same amount.The rate of increase in the core CPI is expected to remain negative for the time being, and to increase in the July–September quarter of 2021 for the first time in six quarters. However, since downward pressure from the supply–demand side remains and falling wages are a factor in lowering service prices, the underlying trend of prices cannot be expected to increase significantly. Core CPI growth rates are forecast to decline 0.4% in fiscal 2020, followed by increases of 0.4% in fiscal 2021, and 0.6% in fiscal 2022.

Please note: The data contained in this report has been obtained and processed from various sources, and its accuracy or safety cannot be guaranteed. The purpose of this publication is to provide information, and the opinions and forecasts contained herein do not solicit the conclusion or termination of any contract.

このレポートの関連カテゴリ

03-3512-1836

経歴

- ・ 1992年:日本生命保険相互会社

・ 1996年:ニッセイ基礎研究所へ

・ 2019年8月より現職

・ 2010年 拓殖大学非常勤講師(日本経済論)

・ 2012年~ 神奈川大学非常勤講師(日本経済論)

・ 2018年~ 統計委員会専門委員

(2021年02月25日「Weekly エコノミスト・レター」)

公式SNSアカウント

新着レポートを随時お届け!日々の情報収集にぜひご活用ください。

新着記事

-

2024年04月18日

サイレントマジョリティ⇒MAGAで熱狂-米国大統領選挙でリベラルの逆サイレントマジョリティはあるか- -

2024年04月18日

「新築マンション価格指数」でみる東京23区のマンション市場動向【2023年】(1)~東京23区の新築マンション価格は前年比9%上昇。資産性を重視する傾向が強まり、都心は+13%上昇、タワーマンションは+12%上昇 -

2024年04月17日

IMF世界経済見通し-24年の見通しをやや上方修正 -

2024年04月17日

不透明感が高まる米国産LNG(液化天然ガス)輸入 -

2024年04月17日

英国雇用関連統計(24年3月)-失業率は増加し、雇用者数も減少

レポート紹介

-

研究領域

-

経済

-

金融・為替

-

資産運用・資産形成

-

年金

-

社会保障制度

-

保険

-

不動産

-

経営・ビジネス

-

暮らし

-

ジェロントロジー(高齢社会総合研究)

-

医療・介護・健康・ヘルスケア

-

政策提言

-

-

注目テーマ・キーワード

-

統計・指標・重要イベント

-

媒体

- アクセスランキング

お知らせ

-

2024年04月02日

News Release

-

2024年02月19日

News Release

-

2023年07月03日

News Release

【Japan’s Economic Outlook for FY 2020–2022】【シンクタンク】ニッセイ基礎研究所は、保険・年金・社会保障、経済・金融・不動産、暮らし・高齢社会、経営・ビジネスなどの各専門領域の研究員を抱え、様々な情報提供を行っています。

Japan’s Economic Outlook for FY 2020–2022のレポート Topへ

各種レポート配信をメールでお知らせ。読み逃しを防ぎます!

各種レポート配信をメールでお知らせ。読み逃しを防ぎます!